Dawn of The Flying Murder Heads

Posted by Richard Conniff on May 15, 2018

By Richard Conniff/National Geographic

Heading out into the geological layer cake of Big Bend National Park in southwestern Texas, British pterosaur researcher Dave Martill proposes a “to do” list for this brief reconnaissance: 1.) Find a rattlesnake to admire. 2.) “Find a complete Quetzalcoatlus skull sitting on the ground.” The odds are almost infinitely better for item one. But he and Nizar Ibrahim, a fellow paleontologist, promptly fall into a detailed discussion about how to obtain a research permit in the event of item two.

This is the first rule of pterosaur research: You need to be an optimist. Thinking you will go out on a given day and find any trace of pterosaurs—the winged dragons that ruled Mesozoic skies for 162 million years–is like buying a Powerball ticket and expecting to win. Pterosaur fossils are vanishingly rare. Their whole splendid world, built on hollow bones with paper-thin walls, has long since collapsed into dust. Scarcity is especially the rule for Quetzalcoatlus northropi, thought to be one of the largest flying animals that ever lived, nearly as tall as a giraffe, with a 35-foot wingspan, and a likely penchant for picking off baby dinosaurs. It’s known from a few fragments discovered at Big Bend in 1971, and not much else.

Martill and Ibrahim spend three days bone-hunting among the fissured hillsides. They cross and re-cross the promisingly named “Pterodactyl Ridge,” frequently consulting the “x-marks-the-spot” on maps left by the discoverer of Quetzalcoatlus. They decipher the nuances of geological strata (“Look at that Malinkovitch-controlled cyclicity!” Martill exclaims, referring to the way the Earth’s shifting movements show up in the rock), and they conjure up forgotten worlds. On a sandstone ridge with no obvious way down, Martill remarks, “Haven’t found a mountain yet we can’t fall down,” plunges forward, and emerges unscathed below, eyes fixed on the passing landscape.

They do not, however, stumble across any rattlesnakes, nor even the faintest whiff of a pterosaur. The femur of an Alamosaurus, the largest North American dinosaur that ever lived, turns up, by way of consolation. But dinosaurs are not pterosaurs, or vice versa. Leaving the park, the two paleontologists are already mapping out a return search for Quetzalcoatlus, permanently hooked on the tantalizing pterosaur mix of extreme biological richness glimpsed through the rarest of fossil remains.

##

Optimism against all odds has, however, lately begun to look almost reasonable in pterosaur research, with a rush of discoveries revealing

surprising new shapes, sizes, and behaviors. Some paleontologists now suspect that hundreds of pterosaur species may have lived at any one time, dividing up habitats much as modern birds do. Their world wasn’t just about monsters like Quetzalcoatlus, but also about pterosaurs the size of sparrows that flitted through primeval forests and fed on insects, pterosaurs that stayed on the wing across oceans for days at a time like albatrosses, and pterosaurs that just stood in briny shallows and filter-fed like pink flamingoes.

The recent discoveries have included not just clutches of eggs, but a community of them, with a new study from China reporting 200 eggs together, and evidence that pterosaurs may have returned to the same nesting site over hundreds of thousands of years. (To put this in perspective, until 2014, just three eggs were known from more than two centuries of pterosaur science.) CT scans of intact eggs have revealed the world of embryos inside the shell and helped to explain how the hatchlings developed. One egg even turned up in the oviduct of a Darwinopterus pterosaur from China, along with another egg apparently pushed out by the impact that killed her. “Mrs. T” (for Mrs. Pterosaur) thus became the first pterosaur indisputably identified by gender. Because she lacked a head crest, while many other Darwinopterus have them, she also provided the first solid evidence that for some pterosaurs, as for some modern birds, big, brightly colored crests probably functioned as a male sexual display device. These discoveries have given pterosaurs a vivid new life as real animals. They’ve also given paleontologists an insatiable appetite for more.

But apart from paleontologists, hardly anyone else seems to have noticed: Most people still respond to the word “pterosaurs” with a puzzled expression, until you add “like pterodactyls.” That’s the common name given to the first pterosaur discovered in the eighteenth century. Scientists have since described more than 200 pterosaur species, but popular notions about pterosaurs have remained stuck: We almost invariably imagine them as pointy-headed, leather-winged, clumsily aerial reptilians, with murderous proclivities.

Habib, who works at the Los Angeles Natural History Museum, set out to reconsider pterosaur biomechanics, combining an intensely mathematical approach with hands-on anatomical knowledge from his other job: teaching in the human cadaver lab at the University of Southern California medical school. (“I need to dissect something,” he explains, “and you can’t dissect a pterosaur.”)

Like most researchers, Habib figures the first pterosaurs emerged roughly 230 million years ago from light, strong reptiles adapted for running and leaping after prey. Jumping—to catch an insect or dodge a predator–evolved into “jumping and not coming down for a while,” Habib theorizes. Pterosaurs probably glided at first. And then, tens of millions of years before birds or bats, they became the first vertebrates to achieve powered flight.

With the help of aeronautical equations that they applied for the first time to biology, Habib and his fellow biomechanists dismissed the cliff-hanging hypothesis. They also demonstrated that taking off from land with an upright, bipedal stance, as other researchers had proposed, would have shattered the femurs of larger species. Launching from a four-point stance made more sense, says Habib. “You want to get over the forelimbs and punch up into the air, like a pole-vaulter.” To take off from water, on the other hand, marine pterosaurs used their wings like paddles to push off the surface and flap into the air “like Michael Phelps doing a butterfly stroke,” Habib says. And like Phelps, they had big, muscular shoulders—often combined with “freakishly small feet” on their hind limbs to minimize drag.

Pterosaur wings consist of a membrane attached to each flank from shoulder to ankle, and held out by a spectacularly elongated fourth finger running along the wing’s leading edge. Beautifully preserved specimens from Brazil and Germany revealed that the wing membrane was threaded with muscles and blood vessels, and reinforced with fibrous cords.

Researchers now think pterosaurs could make subtle adjustments to the shape of the wings in different flight conditions by contracting the wing muscles or by moving their ankles in and out. Changing the angle of a wrist bone called the pteroid may have given them the equivalent of the leading edge slats on a passenger jet, for increased lift at low speeds. Pterosaurs also devoted more muscle to the business of flying, and a larger proportion of their body weight, than do birds, and a larger proportion of their body weight. Even their brains appear to have evolved for flight, with enlarged lobes for processing complex sensory data from the wing membrane.

The result is that pterosaurs have begun to look less like a train wreck in the sky and more like sophisticated aviators. Many species appear to have evolved for flying slowly but with great efficiency for long distances and for soaring on the weak thermals over oceans. A few may even have been “hyper-aerial,” according to Habib. For instance, Nyctosaurus, an albatross-like marine pterosaur with a nine-foot wingspan, had a glide ratio—the distance it could travel forward for every meter of drop—“well within the range of a modern sailplane, things that we have manufactured to be high-efficiency soaring planes,” says Habib.

“OK, the wing stuff is good,” a paleontologist remarked after a recent talk by Habib. “But what is up those heads?” Quetzalcoatlus, for instance, is thought to have had a skull up to ten feet long on a torso a quarter of that length. Nyctosaurus had an outsize head, plus a huge mast sticking out of the top, possibly with a crest attached. It looks like something Dr. Seuss invented.

Habib’s reply has to do partly with pterosaur brains, which added minimal weight to those huge heads. It also has to do with pterosaur bones, which were hollow, like bird bones, only more so. The bone walls were just a fraction of an inch thick, made of crisscrossing, laminated layers to resist bending and breaking—some researchers call them “plywood bones”–and they had struts across the hollow middle, to prevent buckling. That allowed pterosaurs to balloon out the bone, expanding certain anatomical features without adding much weight.

Their skulls, ornamented with crests and keels, and those great, gaping mouths, thus achieved proportions Habib calls “ridiculous,” even “stupid.” It has led him to a sort of Big Bad Wolf hypothesis: “A big head gives you a big mouth, which is good for eating things,” he says. “And a big head is good for sexual display.” Pterosaurs, he told his questioner at that talk, “were giant flying murder heads.”

##

On a busy street in downtown Jinzhou, a commercial hub for northeastern China, an SUV pulls over to the curb and a couple of paleontologists pile out. They head into an ordinary office building, up the stairs, and uncertainly down dimly lit hallways, ending up on the third floor, in the office of the director of the Jinzhou Paleontological Museum. A large artillery shell stands against one wall, and there’s not much else obviously paleontological about the place, except for the presence on the couch of Junchang Lü, a gangling figure with an easy grin, dressed for fieldwork in gray slacks and a red windbreaker.

Lü, who’s on a flying visit from Beijing, follows the museum director down another darkened hallway. The door of a windowless little storage room swings open to reveal what would be any other museum’s star attractions: slabs of stone containing exquisitely detailed fossils of feathered dinosaurs, primitive birds, and especially pterosaurs, covering every inch of shelf and most of the floor.

Propped against the back wall, a slab that comes almost up to Lü’s shoulder displays an alarmingly large pterosaur, a Zhenyuanopterus, with a 13-foot wingspan and tiny chicken feet on its hind legs. The long, thin head, turned to one side, is all basket mouth, a cross-stitching of needle teeth that become longer and overlap out at the killing end. For catching fish while swimming on the surface, says Lü. It’s one of almost 30 pterosaur species he has described since 2001, with others still awaiting scientific recognition on the shelves.

The Jinzhou museum turns out to be one of ten or so such fossil museums scattered around Liaoning Province, the motherlode of modern pterosaur discovery and part of China’s recent rise to the forefront of fossil hunting. Other paleontologists whisper that it’s also the Wild West, with enterprising farmers doing much of the collecting, to the detriment of scientific research. Commercial collectors often buy up prize specimens to sell illegally into the international trade.

In addition, Liaoning is also the main collecting site in a rivalry outsiders liken, a little unfairly, to the notorious nineteenth-century “Bone Wars” combat between pioneering American paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope. This rivalry pits Lü of the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences against Xiaolin Wang, whose specimen-crammed office is at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing. Like Marsh and Cope, the two worked together in the beginning, then went their separate ways in a spirit of muted hostility. (“One mountain cannot contain two tigers,” says Shunxing Jiang, a paleontologist who works at IVPP. It is proverbial.)

In the 16 years since then, each has repeatedly one-upped the other, producing a combined total of more than 50 new pterosaur species—almost a quarter of all known pterosaurs–often with headline-making details, from Lü’s “Mrs. T” to Wang’s 200 Hamipterus eggs. Some of those species will perhaps turn out to be invalid, as happens after every great burst of paleontological discovery: New evidence, or further study, may reveal, for instance, that a supposed new species is really just the adult form of a species someone else has already described based on a juvenile specimen. But each side also has many more discoveries still to come.

“They’d have to work 9 to 5 for 10 years” to describe what they already have on hand, an outsider remarks, enviously. Hearing this, Jiang lifts his eyebrows, a little anxiously, and says, “I think ten years is not enough.”

The Bone Wars comparison is, however, a stretch, given the in-fighting that’s common in this contentious, esoteric field. “We’re a very small group, and we don’t really get along,” one pterosaur specialist remarks. The field, says another, “has a reputation for people who viciously despise one another.” Pterosaur researcher A will readily volunteer that B is “a waste of carbon,” while C independently remarks of A that certain people “would happily see him at the bottom of the ocean.” North American D meanwhile “doesn’t like anybody very much.” Their combat is a natural byproduct of all those optimistic hypotheses built on fragmentary evidence. And it makes the Chinese rivalry look like a tea part. Lü shrugs off talk of mutual loathing, and Wang manages to avoid talking about it at all.

Their success, in any case, probably has as much to do with being in the right place at the right time as with competition: China is one of just five places in the world—together with Germany, Brazil, the United States, and England–that have produced 90 percent of all pterosaur fossils. That’s not because those five were the only places pterosaurs existed in such diversity and abundance. Fragmentary fossils have turned up almost everywhere, even in Antarctica. Instead, paleontologists think the pterosaur diversity that used to exist everywhere else is simply better preserved there, by some quirk of geology.

This is nowhere more beautifully true than in Liaoning. In the early Cretaceous, says Lü, Liaoning’s temperate forests and shallow freshwater lakes supported a rich ecological community, including dinosaurs, early birds, and a large variety of pterosaurs. Violent storms and ashy volcanic eruptions now and then killed some animals suddenly and in large numbers, perhaps slamming them out of the air onto the mudflats. These catastrophic events buried the victims quickly, sometimes anaerobically, with sediments that have preserved specimens intact and in fine detail for more than 100 million years. Paleontologists call such sites “lagerstätte,” from the German meaning roughly a “storehouse” of lost life.

The results now turn up on hilly farms and eroding cliff faces all over Liaoning. They don’t look like much at first, a slab with a hint or two of bone. But after a preparator working at a microscope has meticulously removed eons of hardened crud, they begin to take shape again. To a beginner’s eye, they look as if someone has played pick-up-sticks with an odd assortment of lizard skulls and walking poles. Or as if Wile E. Coyote has gone off a ski slope and gotten squashed flat beneath a huge boulder Road Runner pushed down just behind him: Legs akimbo, mouth agape, head pulled back by the contraction of powerful neck and back muscles, long, bony wing fingers all higgledy-piggledy askew.

When you look at them one after another, though—at, say, the Beipiao Pterosaur Museum, or at a recent pterosaur show at the Beijing Natural History Museum–the fossils begin to make sense as individual species, in all their former diversity. There’s a widemouthed, frog-faced pterosaur named Jeholopterus (also known as the “Cookie Monster” pterosaur), thought to have snapped up dragonflies and other insects in ancient forests. There’s Ikrandraco, named for the aerial mountain banshees in the movie “Avatar” and thought to have flown low over the water, using a sort of keel on its lower jaw to skim beneath the surface for fish. There’s Dsungaripterus, from northwestern China, with a long, thin, upturned beak, for probing for shellfish and other invertebrates, to be crushed up by its knobby molars.

The sight of so many weapons, so much hunger, such vibrant life now frozen in stone, is unmistakably poignant. Something about pterosaurs ultimately made them vulnerable. Maybe the food they depended on vanished during the great extinction at the end of the Cretaceous, 66 million years ago. Or maybe their evolution to increasingly gigantic size left the likes of Quetzalcoatlus vulnerable, whereas some smaller birds and bats could hide out during the catastrophe. For pterosaurs, in any case, it was the end-time.

But as you study their beautifully-preserved remains in a museum, something peculiar happens: You start to wonder if Nemicolopterus, a little insect eater, is sidling off the edge of its piece of shale, as if in pursuit of missing body parts. You wonder if you just saw the toe bones of Kungpengopterus, dark brown and standing out on the rock surface like embossed lettering, begin to twitch. By a trick of the eye or the mind, it can seem–at least momentarily–as if the pterosaurs, this bizarre and bountiful expression of the great driving life force of the planet Earth, might yet rise up from the rock and again take wing.

END

Richard Conniff is the author of “The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth,” and other books.

Charndrey said

Amazing.

LikeLike

daveunwin said

Oh, I just can’t decide, would I rather be ‘a waste of carbon’, or at ‘the bottom of the ocean’, hmmm… and I’m bitterly disappointed that there is no mention of the forward pointing pteroid, an idea that is not dead, its just restin’…

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

Honored to have a comment from the University of Leicester’s David Unwin, easily the most revered “waste of carbon” in the world of pterosaur research. So sorry about the forward pointing pteroid, David.

LikeLike

David M Martill said

You shouldn’t be too honoured. He calls me constantly. Can’t get rid of him… I have to pretend to miss my train if I don’t dash

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

I think I was right about you pterosaur people.

LikeLike

Links 6/5/18 | Mike the Mad Biologist said

[…] Wald and the Missing Bullet Holes Dawn of The Flying Murder Heads Boston vs. the rising tide As Twitter explodes, Eric Lander apologizes for toasting James Watson […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

Death of a Fossil Hunter « strange behaviors said

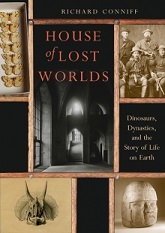

[…] You can read my story about pterosaurs for National Geographic here, resulting in part from my visit with Junchang in December 2016. That trip also resulted in a cover […]

LikeLike