Turns Out Wolves Really Do Change Rivers, After All

Posted by Richard Conniff on March 10, 2014

UPDATE FRIDAY MARCH 30: At the suggestion of a reader, I’m changing the title of this item–formerly “Maybe Wolves Don’t Change Rivers, After All” to reflect the consensus of scientific research noted in my updates before and after this article.

UPDATE MONDAY FEBRUARY 19 2018, new study supports the hypothesis that wolves have changed the character of stream-side vegetation at Yellowstone.

UPDATE SATURDAY MARCH 25 2016: PLEASE NOTE THAT ARTHUR MIDDLETON (below) and all other ecological researchers agree that reintroducing wolves to their former home range across the American West is a major benefit to wildlife and healthy habitats. It is also essential. All this article says is that the results are not as quick or simple as some environmentalists want to believe:

The story of how wolves transformed the Yellowstone National Park landscape, beginning in the 1990s, has become a favorite lesson about the natural world. A video recounting (above) has gone viral lately, with British writer George Monbiot re-telling the story in his best breathy David Attenborough.

The only problem, according to field biologist Arthur Middleton, writing in today’s New York Times, is that it isn’t true.

I don’t like the NYT headline “Is the Wolf A Real American Hero?” which seems to fault the wolf for our myth making. But otherwise, this op-ed is a good reminder that nature is almost always more complex than the stories we tell about it :

FOR a field biologist stuck in the city, the wildlife dioramas at the American Museum of Natural History are among New York’s best offerings. One recent Saturday, I paused by the display for elk, an animal I study. Like all the dioramas, this one is a great tribute. I have observed elk behavior until my face froze and stared at the data results until my eyes stung, but this scene brought back to me the graceful beauty of a tawny elk cow, grazing the autumn grasses.

As I lingered, I noticed a mother reading an interpretive panel to her daughter. It recounted how the reintroduction of wolves in the mid-1990s returned the Yellowstone ecosystem to health by limiting the grazing of elk, which are sometimes known as “wapiti” by Native Americans. “With wolves hunting and scaring wapiti from aspen groves, trees were able to grow tall enough to escape wapiti damage. And tree seedlings actually had a chance.” The songbirds came back, and so did the beavers. “Got it?” the mother asked. The enchanted little girl nodded, and they wandered on.

This story — that wolves fixed a broken Yellowstone by killing and frightening elk — is one of ecology’s most famous. It’s the classic example of what’s called a “trophic cascade,” and has appeared in textbooks, on National Geographic centerfolds and in this newspaper. Americans may know this story better than any other from ecology, and its grip on our imagination is one of the field’s proudest contributions to wildlife conservation. But there is a problem with the story: It’s not true.

We now know that elk are tougher, and Yellowstone more complex, than we gave them credit for. By retelling the same old story about Yellowstone wolves, we distract attention from bigger problems, mislead ourselves about the true challenges of managing ecosystems, and add to the mythology surrounding wolves at the expense of scientific understanding.

The idea that wolves were saving Yellowstone’s plants seemed, at first, to make good sense. Many small-scale studies in the 1990s had shown that predators (like spiders) could benefit grasses and other plants by killing and scaring their prey (like grasshoppers). When, soon after the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone, there were some hints of aspen and willow regrowth, ecologists were quick to see the developments through the lens of those earlier studies. Then the media caught on, and the story blew up.

However, like all big ideas in science, this one stimulated follow-up studies, and their results have been coming in. One study published in 2010 in the journal Ecology found that aspen trees hadn’t regrown despite a 60 percent decline in elk numbers. Even in areas where wolves killed the most elk, the elk weren’t scared enough to stop eating aspens. Other studies have agreed. In my own research at the University of Wyoming, my colleagues and I closely tracked wolves and elk east of Yellowstone from 2007 to 2010, and found that elk rarely changed their feeding behavior in response to wolves.

Why aren’t elk so afraid of the big, bad wolf? Compared with other well-studied prey animals — like those grasshoppers — adult elk can be hard for their predators to find and kill. This could be for a few reasons. On the immense Yellowstone landscape, wolf-elk encounters occur less frequently than we thought. Herd living helps elk detect and respond to incoming wolves. And elk are not only much bigger than wolves, but they also kick like hell.

The strongest explanation for why the wolves have made less of a difference than we expected comes from a long-term, experimental study by a research group at Colorado State University. This study, which focused on willows, showed that the decades without wolves changed Yellowstone too much to undo. After humans exterminated wolves nearly a century ago, elk grew so abundant that they all but eliminated willow shrubs. Without willows to eat, beavers declined. Without beaver dams, fast-flowing streams cut deeper into the terrain. The water table dropped below the reach of willow roots. Now it’s too late for even high levels of wolf predation to restore the willows.

A few small patches of Yellowstone’s trees do appear to have benefited from elk declines, but wolves are not the only cause of those declines. Human hunting, growing bear numbers and severe drought have also reduced elk populations. It even appears that the loss of cutthroat trout as a food source has driven grizzly bears to kill more elk calves. Amid this clutter of ecology, there is not a clear link from wolves to plants, songbirds and beavers.

Still, the story persists. Which brings up the question: Does it actually matter if it’s not true? After all, it has bolstered the case for conserving large carnivores in Yellowstone and elsewhere, which is important not just for ecological reasons, but for ethical ones, too. It has stimulated a flagging American interest in wildlife and ecosystem conservation. Next to these benefits, the story can seem only a fib. Besides, large carnivores clearly do cause trophic cascades in other places.

But by insisting that wolves fixed a broken Yellowstone, we distract attention from the area’s many other important conservation challenges. The warmest temperatures in 6,000 years are changing forests and grasslands. Fungus and beetle infestations are causing the decline of whitebark pine. Natural gas drilling is affecting the winter ranges of migratory wildlife. To protect cattle from disease, our government agencies still kill many bison that migrate out of the park in search of food. And invasive lake trout may be wreaking more havoc on the ecosystem than was ever caused by the loss of wolves.

When we tell the wolf story, we get the Yellowstone story wrong.

Perhaps the greatest risk of this story is a loss of credibility for the scientists and environmental groups who tell it. We need the confidence of the public if we are to provide trusted advice on policy issues. This is especially true in the rural West, where we have altered landscapes in ways we cannot expect large carnivores to fix, and where many people still resent the reintroduction of wolves near their ranchlands and communities.

This bitterness has led a vocal minority of Westerners to popularize their own myths about the reintroduced wolves: They are a voracious, nonnative strain. The government lies about their true numbers. They devastate elk herds, spread elk diseases, and harass elk relentlessly — often just for fun.

All this is, of course, nonsense. But the answer is not reciprocal myth making — what the biologist L. David Mech has likened to “sanctifying the wolf.” The energies of scientists and environmental groups would be better spent on pragmatic efforts that help people learn how to live with large carnivores. In the long run, we will conserve ecosystems not only with simple fixes, like reintroducing species, but by seeking ways to mitigate the conflicts that originally caused their loss.

I recognize that it is hard to see the wolf through clear eyes. For me, it has happened only once. It was a frigid, windless February morning, and I was tracking a big gray male wolf just east of Yellowstone. The snow was so soft and deep that it muffled my footsteps. I could hear only the occasional snap of a branch.

Then suddenly, a loud “yip!” I looked up to see five dark shapes in a clearing, less than a hundred feet ahead. Incredibly, the wolves hadn’t noticed me. Four of them milled about, wagging and playing. The big male stood watching, and snarled when they stumbled close. Soon, they wandered on, vanishing one by one into the falling snow.

That may have been the only time I truly saw the wolf, during three long winters of field work. Yet in that moment, it was clear that this animal doesn’t need our stories. It just needs us to see it, someday, for what it really is.

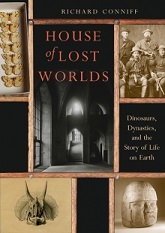

Richard Conniff is an award-winning science writer. His books include The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth (W. W. Norton, 2011). He is now at work on a book about the fight against epidemic disease. Please consider becoming a supporter of this work. Click here to learn how.

UPDATE SATURDAY JANUARY 31 2015: Check out my latest piece on how wolves, bears, and other top predators produce a cascade of effects that change the nature of entire ecosystems.

UPDATE WEDNESDAY OCTOBER 1: Ranchers complain about too many wild horses overgrazing the American West. Could wolves fix that problem?

UPDATE SUNDAY SEPTEMBER 28: A U.S. Forest Service logging proposal threatens the survival of a wolf species in Tongass National Forest on the Alaska Coast. Read the article here.

carlsafina said

I find this article perplexing. While researching a book I’m working on, I spent a week in Yellowstone last winter and spoke at length to Doug Smith who oversaw the wolf re-intro and is still there, and various people who’ve watched the wolves for years. Doug (and his book “Decade of the Wolf”) conveys the same wolf-elk-vegetation story that the writer of this article claims is wrong. Elk might “kick like hell” as the writer says, but the wolves in the park eat mainly elk. Unlike the writer who saw wolves once, in that single week that I was there I saw them daily, often watched them for hours at a time, and saw them on several elk kills. Inside Yellowstone—which is where the writer is talking about even though his research was done outside Yellowstone—elk are what wolves eat. As a PhD ecologist myself, it’s hard to see how 60% fewer elk could affect vegetation as much as before. And either the beaver came back or they didn’t–and apparently they have. I looked at the writer’s two science links and they seem solid enough, though his work is brief, and recent, and mainly outside the park. The science and observation in the park over three decades (actually longer–wolves were extirpated in the 1920s) means something too. Wolves in the park exploded in numbers after reintroduction because elk were super-abundant and naive. Now wolf numbers are down significantly along with elk. It appears things inside the park are still equilibrating. So, again, I find this article perplexing. Yes Yellowstone is broken in other ways, regardless–and yes it matters if the story is true.

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

Thanks, Carl. I hope you forwarded this comment to Doug. It will be interesting to hear his response.

LikeLike

Tristan Chris Heiss said

most likely this writer is just one of those paid by the anti wolf people. the USA is full of liberal ‘academics’ who have been known to lie thru their teeth for 15 minutes of fame.

LikeLike

Nicole Gomes said

❤ thanks for that 😉

LikeLike

Stephen Barraclough (@BasBarraclough) said

I don’t care what the story, someone – often for the best of motives, (& not necessarily just to see his name in print!) always seems to come along to trash it. Especially if it is a ‘nice’ story! Too few nice stories, we seem addicted to gloom and dismay! CHEER UP for God’s sake why don’t you?

LikeLike

Jeff Gates said

Unfortunately, Science is not about being nice. Peer review starts in the comment boards.

LikeLike

Cathie Ellison said

But the video attached to all these comments doesn’t say it is Elk! It states that the DEER population got out of hand.and the re-introduction of wolves helped that problem which led to many other benefits. Less soil erosion etc. That is what I got out of this video… Perhaps the people purporting that thw wolves didn’t change anything should re-watch and LISTEN more carefully.

LikeLike

Andre said

Elk are a type of deer. I agree that the original post isn’t well-founded, but he isn’t wrong when he makes no differentiation between elk and deer. Moose are also deer. So are caribou.

LikeLike

findheatherlee said

In the Western United States, the specific animals featured in that video are differentiated from deer and called “elk” by people who actually live there.

LikeLike

Paul Geraci said

Taxonomic accuracy is important to those who actually DO science.

LikeLike

Lisa Messmer said

from the youTube page where this video can be found:

NOTE: There are “elk” pictured in this video when the narrator is referring to “deer.” This is because the narrator is British and the British word for “elk” is “red deer” or “deer” for short. The scientific report this is based on refers to elk so we wanted to be accurate with the truth of the story.

LikeLike

Karen Renfro said

It is scientifically correct to call elk, moose or caribou “deer” because these species all belong to the deer family Cervidae–because they are kind of like second-cousins (American Desk Encyclopedia, Oxford). Remember the taxonomic order of life goes like this: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species. I found it interesting to read the above post about the difference between the way Americans and British identify elk.

LikeLike

Sally Hamilton said

They are “called elk” because they are elk. Much different than deer.

LikeLike

Bob Koorse said

Why are so many commenters ignoring the information that for someone from the British Isles, as the narrator in the original piece is, elk= deer. Do you people read before writing?

LikeLike

Sharon Brogan said

Why all the talk about a name? They are what they are, and the wolves eat them. Which is a good thing. Take away an apex predator and everything goes to he**

LikeLike

Sharon Brogan said

Why all the talk about a name? They are what they are, and the wolves eat them. Which is a good thing. Take away an apex predator and everything goes to he**. The video was about changes caused by wolves. Shouldn’t we be talking about the video, instead of one small part in the video?

LikeLike

Bob Koorse said

Well Sharon…and let me say up front I think the original observations regarding the effect of the wolf on that ecosystem are certainly plausible. I admit that I have to be careful to not allow my biases to influence my assessment of conclusions. I have read Mech and others and quite simply admire the animal we call the wolf.

I think the discussion/debate over nomenclature is understandable in a way. Some people don’t know much about the subject going in, and when there is something they consider to be a glaring error, they back off from acceptance or even consideration of the subject matter. I for example, having grown up in NYC, saw deer often when we drove “to the country.” I never saw elk in the wild until I went to Wyoming. To me they are very different animals, but I somehow intuited that the narrator was using the word “deer” in a different way, and not simply making a zoological nomenclature error.

I hope most of the readers who got stuck on the deer-elk thing got unstuck when they read about the difference in common names for these animals depending on which side of the Atlantic the speaker hails from.

You are right that it doesn’t make a difference with respect to the biology/ecology, but we want to bring as may people along in enjoying, understanding and feeling concerned about the very real environmental concerns that are at the heart of this topic. And we do have to include those who honestly question even those premises we believe to be unassailable, as well as those who might be “nitpickers” and feel that an “expert” can’t be much of one if he can’t tell a deer from an elk or heavens to Betsy from a moose.

LikeLike

whendsue said

His statement regarding the one encounter as being the only time he “truly saw the wolf” doesn’t mean it was his only observation of these animals. He is implying, perhaps, that he had otherwise not seen them “through clear eyes”, but with preconceived notions, judgments or other expectations.

LikeLike

Karen Renfro said

When I watched the video on the Wolves at Yellowstone, I was so happy. I was amazed at the unfolding resurrection of wilderness life because of the presence of wolves, but not surprised. When I read “Maybe Wolves Don’t Change Rivers After All”, I was struck by the disorganized way the writer presented his case. But, the main thing he wasn’t in the least convincing as far as I am concerned. I don’t have any idea how many years or decades or centuries or millenia it takes for the various stages of this process to finally reach an equilibrium, or if we have already reached it but it is swinging back and forth according to some natural rhythm of nature I’m not aware of yet. Also, the wolves can’t be everywhere at once so if the elk are running amok in some places at Yellowstone, that doesn’t mean nothing good has changed. It just means that where there are wolves, there is life in abundance for a great many species. And ecological health. Tell me there is no intelligent design in the universe. Thank you all for the wonderful education.

LikeLike

Paul said

On June 15th the House Committee on Natural Resources held a legislative markup on 19 bills and passed two out of committee that would spell disaster for our national public lands.

Rep. Raul Labrador’s (ID) Self-Sufficient Community Lands Act (H.R. 2316) and Rep. Don Young’s (AK) State National Forest Management Act of 2015 (H.R. 3650) would result in the seizure of millions of acres of public lands and threaten the health of our national forest system, fish and wildlife habitat, and public access to quality hunting and fishing.

Contact your members of Congress today and tell them legislation like this doesn’t belong in America – and would compromise the integrity of our proud public lands legacy.

LikeLike

Kendall Coley said

The importance of a hero to rally anecdotally references trickle down shortfalls cumulatively on our planet. As humans we tend to pretend we are outside observers of the natural world which could be deduced as a parasitic perspective. The beauty of the wolves allows us to re-integrate OUR place on this planet as a symbiotically viable species.. Bravo to the wolf!

LikeLike

Kevin Carvell said

Arthur Middleton makes a significant error in saying that the argument that wolves kill elk is without merit. But the point that the video makes is that wolves kill deer. One isn’t much of a field biologist if you mistake deer for elk.

LikeLike

Richard G said

I echo your thoughts, I’ve seen the video and when I began reading this writers argument and he is referring to elk, I thought, geeze, does this guy know the difference between and elk and a deer? Growing up in Iowa, where the deer are in large numbers, I have seen the destruction of parks and fields from the deer and the benefits of thinning the heard. Arthur needs to educate himself on some significant differences.

LikeLike

Andre said

Elk are deer. So are moose and caribou.

LikeLike

Tristan Chris Heiss said

Pat Kennedy said

October 12, 2014 at 10:33 am

Tom Stevens is right. Moose are moose, elk are elk, deer are deer..differentiated between red deer, sika etc etc. However not once have I read in any of the comments below or up that this video does not convey any elk…. The speaker doesn’t mention elk nor does he show elk in the video. So, whether it is an error to leave the elk population out of the equation or for this type of single species promotion it was necessary to do that, I don’t know. But wolves remain amazing creatures and a key element to the food chain. Yellowstone, and any other part of this earth constantly changes, naturally or chemically induced by the overpopulation of humans or the earth’s own regeneration…in order to find the balance not only there, but here too, we need a better ecosystem ourselves.. My rebuttal…all the 4 legged herbivores in the video are ELK, every last one..obviously you don’t know an ELK from a white tail deer?

LikeLike

Lisa Messmer said

From the youTube page where this video can be found:

NOTE: There are “elk” pictured in this video when the narrator is referring to “deer.” This is because the narrator is British and the British word for “elk” is “red deer” or “deer” for short. The scientific report this is based on refers to elk so we wanted to be accurate with the truth of the story.

LikeLike

Bob Koorse said

thank you. Now can you print this in bold or NEON, so the people still objecting on the basis of what you (and others, already) have fully explained, will stop?

LikeLike

Lisa Messmer said

I wish I could. Maybe this little blurb I took from the original youtube video should be put in the opening paragraphs of this article, in quotation marks with reference to the original video, and in bold font, so that it cannot possibly be missed except the most idiotic of readers. But even then, I fear the complaints would continue. So goes the dumbing down of America. I don’t understand why the author of this article doesn’t take the responsibility to point this out to the readers, since this is complained about over and over again. It’s not my job, nor yours, to correct those who are too lazy to read the comments or look up the facts for themselves. I don’t get it. It would be a small matter, it seems, to edit the article and set forth the facts explaining the confusion so many are having.

LikeLike

Katina Choiniere said

@Kevin Carvell. Elk are deer.

LikeLike

Brian Wilkins said

No, they aren’t. There are many species of ‘deer’, but Elk is it’s own species. They are in the same Family, but is like saying Moose are deer.

LikeLike

Brian Wilkins said

I’ll retract that, as further looking into it, the common name for the family is ‘deer’.

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

Also bear in mind that the speaker is a Brit, and they have different terminology for elk, moose, etc.

LikeLike

Tom Stevens said

I’m a Brit, we don’t have elk or moose in the UK but we do have deer, and we know there are more than terminology” differences between them. If someone says deer I think deer, if someone says moose I think moose.

LikeLike

Andre said

The fact remains, elk are a type of deer. You might be unaware of this, but people who think a lot about elk–and moose and caribou–are well aware that they are species of deer.

LikeLike

Karen Fischer said

Pertaining to whether or not Elk are deer: according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary –“any member of the deer family, Cervidae, comprising deer, caribou, elk, and moose, characterized by the bearing of antlers in the male or in both sexes.”

LikeLike

Max said

A møøse once bit my sister

LikeLike

James Berry said

Elk, Deer, moose are all grazing animals and wolves prey on each of them. I think the point the video was trying to make was overgrazing and the damage it causes, the particular type of grazing animal is erroneous.

LikeLike

Pat Kennedy said

Tom Stevens is right. Moose are moose, elk are elk, deer are deer..differentiated between red deer, sika etc etc. However not once have I read in any of the comments below or up that this video does not convey any elk…. The speaker doesn’t mention elk nor does he show elk in the video. So, whether it is an error to leave the elk population out of the equation or for this type of single species promotion it was necessary to do that, I don’t know. But wolves remain amazing creatures and a key element to the food chain. Yellowstone, and any other part of this earth constantly changes, naturally or chemically induced by the overpopulation of humans or the earth’s own regeneration…in order to find the balance not only there, but here too, we need a better ecosystem ourselves..

LikeLike

Andre said

Um…Pat, somebody just posted the definition of deer from the Miriam Webster dictionary. Didn’t you see that? It’s three posts above yours. It states that both elk and moose are species of deer.

Because of this fact–the fact that elk and moose are species of deer–it’s very common, even in science writing written at the popular level, to refer to elk and moose as deer.

LikeLike

Karen Renfro said

A Species descends from a Genus, the same way you descend from your parents. A Genus descends from a Family the same way your parents descend from your grandparents. A Family descends from an Order the way your grandparents descend from your great-grandparents, and so on up the taxonomic order. Everyone who shares any pair of parents, or grandparents, or great-grandparents are kin. If your paternal great-grandfather was named Smith, it is nevertheless correct to call any and all of his descendents who do not share the same surname a member of the Smith family. That is why it is correct to identify a North American elk as a deer. This is natural science. Read the posts below!

LikeLike

Tom said

So, in the UK there are Red Deer. Elk, for many years were classified as a subspecies of Red Deer, though some biologists had suggested it sufficiently different from a European Red Deer to be individually classified as far back as the 18th Century. However it didn’t become official until the mid 1990’s. Nevertheless, Elk is a species of deer; it belongs to the Familia Cervidae, derived from the Latin word Cervus, which means Deer.

LikeLike

Bob Koorse said

to Max said: Oh dear! I hope the poor deer is ok.

LikeLike

Tracie said

The video doesn’t even mention elk.

LikeLike

Bill Gaw said

Your point?

LikeLike

weseld1 said

But the video shows elk every time it is talking about deer, The legalistic arguments that they are all “deer” is like saying that it does not matter if we hunt the wolves to extinction, because we will still have plenty of dogs, and wolves are just dogs. This lack of precision in the script just gives critics of the film a stick with which to beat it. I agree that reintroduction of wolves has been good for Yellowstone, and may have caused some of the indirect effects claimed by the video. But making over-the-top claims that cannot be substantiated by real evidence (like “Both polar ice caps will have disappeared by 2010”) is too likely to backfire and discredit the true parts of the story. I fear that the producers of the video are indeed, Crying Wolf.

LikeLike

Andre said

Elk are a type of deer, so there is no lack of precision.

LikeLike

Andre said

“The legalistic arguments that they are all “deer” is like saying that it does not matter if we hunt the wolves to extinction, because we will still have plenty of dogs, and wolves are just dogs.”

Why is this the case?

To me it seems that referring to elk as a type of deer, which they are, is the same as simply referring to a coyote as a type of canid, which they are. You, personally, might want more precision, but there is no fallacy here. Say we had a video, the point of which is to show that wild canids are in the habit of killing white tailed deer in a certain area. And imagine this video showedo a coyote killing a small white-tail deer. And imagine the narrator of the video said, “Here we have a wild canid killing a white-tail deer.” Is the narrator wrong in calling the coyote a canid? No. Is there anything wrong with the fact that he didn’t specify that this particular canid was a coyote? No. The fact that he didn’t specify leaves open the idea that there could be other types of wild canids killing white-tail deer in the area. Just as, in the actual video under discussion, the idea is left open that there could be other kinds of deer being killed in Yellowstone, besides just elk. I wouldn’t doubt that this was left open on purpose, since there are other types of deer in Yellowsone, and they are all prey for wolves.

The only problem I can see here is that some people don’t happen to know that elk are simply a type of deer. But that’s not due to any bad narration, that’s due to ignorance on the part of the viewer.

LikeLike

Andre said

In other words, there are all kinds of deer being preyed upon by wolves in Yellowstone, but the video only showed one kind of deer. There is nothing wrong with this. Unless you think that they should show every single kind of deer being preyed upon in Yellowstone. That seems silly to me.

LikeLike

Lisa Messmer said

NOTE: There are “elk” pictured in this video when the narrator is referring to “deer.” This is because the narrator is British and the British word for “elk” is “red deer” or “deer” for short. The scientific report this is based on refers to elk so we wanted to be accurate with the truth of the story.

LikeLike

Philip Ritter said

European elk are what we Americans call “moose” (Alces alces). The pictures with the video clearly show what we call elk (Cervus canadensis), which was once considered a subspecies of European red deer but are now considered a distinct species. Thus a British video would be likely to call our elk “deer” since “elk” in Britain means what we call moose. From Wikipedia’s entry for “elk” (USA version):” this animal should not be confused with the larger moose (Alces alces), to which the name “elk” applies in the British isles and Eurasia.” Wolves do eat elk in Yellowstone (although they may well eat deer also).

LikeLike

Bob Shank Jr. said

Phil Ritter,

Now, that’s a response which makes some serious sense. Well said, sir. And it took me a while to check your research, but I’ve found it accurate wherever I’ve engaged myself, online or otherwise.

~Bob Shank, Tucson AZ

LikeLike

Nicole Gomes said

This article reminded me of the.movie the Life of Pi!!! Some people prefer the horrible side of every history!!!! Some people prefer the beauty of the magic of life in all aspects!!! We need to have wolf controlling these bad species too 😉 Viva los wolves!!! And Elks and Deers and Moose hehehe

LikeLike

Flynnmiller said

What’s interesting in this article are several points that have nothing to with the author’s field of expertise but in how humans will percieve information. He is no more qualified that anyone to asert that crediting wolves is bad for our perception of wildlife. Perhaps a victory here or there is GOOD for human view of the environment, for if we cannot win then why should we try?

LikeLike

Karen Renfro said

Thank you. Reminds me a little bit of God’s opinion of his creation. And no, I don’t think the universe is six thousand years old.

LikeLike

Oak Tree Lady (@Upintheoaks) said

I was enjoying this until you dumped the big lie, “The warmest temperatures in 6,000 years” as an “important conservation challenge” on us! How can I believe one word you say now? Go fly a kite, and try to stay away from the beheading Islamic terrorists.

LikeLike

meronjo said

@ Oak Tree Lady, I too was concerned about the “The warmest temperatures in 6,000 years” comment and it caused me to question the articles integrity. HOWEVER, I do not at all understand your reference to “beheading Islamic terrorists.” The two issues are totally unrelated and now your own bias, phobias and integrity is in question. Not sure if yours was sarcasm or a serious attempt to connect these two extremely different topics but, either way, I thought your comment was ugly and entirely irrelevant.

LikeLike

Tristan Chris Heiss said

not as irrelevant as your liberal arts degree

LikeLike

Bob Koorse said

For those who haven’t picked up on it yet, Tristan Chris Heiss is a white supremacist. I may be using the term a bit loosely, but simply check out his Facebook page. If you look at some of his posts you’ll perhaps have a laugh at him with me at the irony of his showing up here…Strange Behaviors!

LikeLike

Mark Choi said

Being that these actually are the warmest temperatures in 6,000 years, what on earth is your point?

LikeLike

Mark Choi said

And please don’t bring the Mid-Holocene Climatic Optimum myth up, this is supposed to be a serious, fact-based discussion, not a regurgitating of right wing nonsense unsubstantiated by actual science.

LikeLike

Tristan Chris Heiss said

hmm 6000 years huh? considering several inventors invented a version of the thermoscope at the same time. In 1593, Galileo Galilei invented a rudimentary water thermoscope, which for the first time, allowed temperature variations to be measured. I’d say your statement on the time frame is irrelevant . I’d also say you need to look into the fraud that is global warming now known a s climate change ,tomorrow who knows what it will be called because the leftists seem to think changing a things name will change its meaning..sort of like homosexual to gay, or communist to progressive,etc.

LikeLike

Rahim Bugo said

Elk are tough doesn’t argue scientifically the wolves influence or absence of it on the ecosystem, neither did the the rest of his statements which for a researcher, is written unobjectively. In NZ most reforestation starts in gullies to encourage birds and erosion protection and it’s been working.

Dear Oak Tree Lady, this is unrelated, but I ask you politely to kindly not associate Islam with terrorists, including the nutcases who are beheading people. What they do is wholly un-Islamic and it is as much a contradiction in terms as they are insane. No argument from me, just as a Muslim myself, I have no idea who or what they think they are doing. Peace.

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

Dear Readers: I’m not sure what has provoked the sudden surge of interest in this post, but here are a few other recent articles on this site addressing the issue of wolves in the American West:

Bring Back Wolves … Everywhere: https://strangebehaviors.wordpress.com/2014/06/20/bring-back-wolves-everwhere/

Idaho Steps Up Its Irrational War on Wolves: https://strangebehaviors.wordpress.com/2014/04/26/idaho-steps-up-its-irrational-war-on-wolves/

Getting Ranchers to Tolerate Wolves–Before It’s Too Late: https://strangebehaviors.wordpress.com/2014/02/01/getting-ranchers-to-tolerate-wolves-before-its-too-late/

LikeLike

fureysmom said

The wolf story is circulating on facebook, and your article is coming up below it as related. Hence, the click-throughs. That’s how I got here.

LikeLike

Rahim Bugo said

Same as Fureysmom. I read it to see the argument against the claim.

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

Thank you both. Bit of a surprise to see 10,000 readers suddenly show up. Hope they stop for a look around.

LikeLike

Randy whelchel said

you have no reason to believe but last year in one night just north of Yellowstone a wolf (s) killed 97 out of 187 sheep on one ranch, they did not even eat any.

LikeLike

Greg Sherman said

so what? sheep aren’t an endangered species, sheep can be raised anywhere, wolves can’t live just anywhere, the govt pays ranchers for their losses anyway, so I don’t see that as a reason to eliminate wolves

LikeLike

Harriette Glover said

Seriously @George Sherman responses like “so what?..” beg to be addressed and hopefully, reconsidered. Obviously you have never experienced the joys and pain of hard work associated with farming. Even when the slaughter of half of your flock is “replaced by government subsidies,” it is still a life changing event for all involved when an aggressive non-native predator poaches onto your land outside of the YNP. Expecting cleanup naturally via other carrion species isn’t quite so glamorous as it seems. Most of the kills were wasted, leaving a prolonged exposure risk to the remaining flock and human farm workers to the remains to become a sanitation issue which requires tremendous amount of work. Bureaucratic red tape to actually get subsidized for your losses can make or break a farm. The same farm that has every right to be sharing the environment as the beautiful, but much more aggressive wolves that were brought in from Canada to reign unchallenged near this area. So yes… it really does matter to someone. Someone who works very hard for their small slice of their American dream.

LikeLike

Tristan Chris Heiss said

Harriette? the native species is the wolf..the non-native species is man and his sheep. You sound like you have liberal selective education.

LikeLike

Karen Renfro said

That is too bad about the wolf(s) killing all those sheep for sport. If they weren’t hungry, why would they do it? Does anybody know? Did this ever happen before & when & under what circumstances? They could be rogue-wolves that do not belong to the packs inside Yellowstone, kind of like gangs.

LikeLike

Bob Koorse said

Notice Tristan Chris Heiss’s preoccupation with “liberal issues.” One strange character.

As to the initial comment from Randy W, I mean you no offense but you are correct I don’t believe the story without documentation.

As for the comment by Harriette G, it is well taken. We make a mistake when we think our point of view is the only valid one. Let’s try to see the rancher’s side too. These are some very hard working people.

LikeLike

Paul said

On June 15th 2016 the House Committee on Natural Resources held a legislative markup on 19 bills and passed two out of committee that would spell disaster for our national public lands.

Rep. Raul Labrador’s (ID) Self-Sufficient Community Lands Act (H.R. 2316) and Rep. Don Young’s (AK) State National Forest Management Act of 2015 (H.R. 3650) would result in the seizure of millions of acres of public lands and threaten the health of our national forest system, fish and wildlife habitat, and public access to quality hunting and fishing.

Contact your members of Congress today and tell them legislation like this doesn’t belong in America – and would compromise the integrity of our proud public lands legacy.

LikeLike

Dee said

Adult elk might be strong and kick hard, but predators tend to kill the young, elderly, weak, and ill. which does keep prey numbers in check.

LikeLike

Nordlyst said

Good point. Also, it is NOT claimed in the video that the number of kills was a significant factor. To the contrary, the claim is that the wolves affected grazing mainly because their presence changed the BEHAVIOR of the deer.

LikeLike

Karen Renfro said

Thank you.

LikeLike

Becky said

Attenborough didn’t say one word about Elk.

LikeLike

Nordlyst said

What’s more, Attenborough didn’t say one word about anything at all.

Read the first sentences of this post again if you fail to see what I mean. 🙂

LikeLike

Lisa Messmer said

That gave me a laugh.

LikeLike

Paul said

On June 15th 2016 the House Committee on Natural Resources held a legislative markup on 19 bills and passed two out of committee that would spell disaster for our national public lands.

Rep. Raul Labrador’s (ID) Self-Sufficient Community Lands Act (H.R. 2316) and Rep. Don Young’s (AK) State National Forest Management Act of 2015 (H.R. 3650) would result in the seizure of millions of acres of public lands and threaten the health of our national forest system, fish and wildlife habitat, and public access to quality hunting and fishing.

Contact your members of Congress today and tell them legislation like this doesn’t belong in America – and would compromise the integrity of our proud public lands legacy.

LikeLike

MiMi said

The whole article makes me chuckle a bit. If you spent anytime in the country as a kid, this is common sense. Don’t need scientist to tell me something I’ve seen first hand over time. Now let everybody argue about it….those of us who know this is pretty much how nature works on a 365/24/7 basis will sit back and just “bless your hearts”…..Sometime folks are just too smart for their own good. JMHO

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

Ladies and gentlemen, we have a winner in the category “Smug and Obnoxious Comments That Add Nothing to The Discussion.”

LikeLike

Bob said

You post a blog and enable comments. If you can’t handle negative comments either don’t read them or don’t post anything. I agree with most that your argument just doesn’t add up. As others have said, wolves don’t hunt the big elk that could hurt them. Also like you said, why does it matter? The story helps promote conservation. Why argue it?

LikeLike

Peter Flint said

It’s not about whether a story promotes conservation, it should be correct as well. I love more than anything that a video like Monbiot’s beat out this week’s “Krazy Kats Do Krazy Things” video for viral dispersal, but (and here’s an extreme example) if it were a video that discussed the arrival of dinosaur bones 6,000 years ago, I wouldn’t promote it for getting the public interested in palaeontology. It is important for studies to make a point, such as those promoted by Monbiot and the like, but it is just as important that people question them and make forward movement by picking at potential flaws in the argument. Do I agree with everything that Richard has said? Not entirely, but I respect him for making a solid argument and asserting that those who attempt to continue his discussion are on-topic and poignant.

LikeLike

Karen Renfro said

Richard, I can’t see anything smug or obnoxious about Mimi’s comment and I think she has contributed something really worthwhile to this discussion. I do not think I am an expert but I know enough to be able to tell if someone knows what they are talking about. I have great respect for those who have superior knowledge on a subject I’m interested in whether or not they have any formal academic credentials. I think you owe Mimi an apology.

LikeLike

Rork said

And all the deer hunters near me in MI KNOW that wolves need “management” (culling) or they will increase “out of control”. And they know that wolves eating deer means less deer for hunters (they’ve never heard or thought about compensatory vs additive deaths). And that killing predators means more of their prey will result – This is all “obvious” to their blessed little minds. Aldo Leopold (“Game Management” not “Sand”) tells several historical stories to show that doesn’t always happen (usually because of release of some other predator: 1) kill owls to help bob-white in GA, get more rats, get less bob-white, oops, 2) kill red-tails in PA to get more pheasant, get more smaller hawks, the ones actually good at killing pheasants, get less pheasants, oops, and several others). Yeah, us hunters in MI know about wildlife management – right up to the theory around 1920. The reality is that it can be so very complicated.

Read Mech’s paper: “The wolf is neither a saint nor a sinner except to those who want to make it so.” And the who-cares-if-it-is-true-or-not comments really hurt, cause using bad arguments can hurt your cause.

LikeLike

Charlie B said

Yes Rork! And in Wisconsin they have brought in wolves, but guess what? They brought in Canadian wolves that are bigger and more aggressive which yes, IS a problem.

LikeLike

Tim said

If there was a 60% decline in Elk numbers but the Aspen didn’t grow back….those remaining 40% must have increased their consumption of Aspen. Something in this rebuttal doesn’t add up.

LikeLike

sighthndman said

No. The aspen could fail to germinate because of soil conditions, they could fail to grow beyond a minimal size because the water table is too low, the population could fail to grow because of conditions that we didn’t think of, . . . . Aspen don’t fail to thrive and grow merely because they are grazed by elk.

As anyone who has ever tried to grow aspen in their back yard can tell you. They’re pretty easy to kill.

LikeLike

Andy Shambaugh said

I am guessing the writer wrote this article in an attempt to stop the reintroduction of deer somewhere in England. The article seems to have no bases in reality. It hogwash.

LikeLike

Hester said

Reintroduction of deer in England??? The countryside in The Uk is awash with deer.. Red, Roe and Muntjac.

LikeLike

Karen Renfro said

Hmmm…

LikeLike

starmiter said

So, the video I saw actually stated it was deer the wolves were keeping in-check, not elk – is there another video where the narration is different?

LikeLike

starmiter said

Actually, the other comments started to load, and I did get to see how elk & deer are functionally interchangeable, particularly culturally; I do like the ripple-effect nature of the story, though the scientific method demands changing opinions based on a new evidence, and on the surface, at least, the data doesn’t seem to support the story, but I have to agree with the logic problem of a 60% reduction in elk didn’t have a significant impact on tree regrowth – it just seems counter-intuitive that something that should be an inverse proportion has no real change when one side goes down significantly as the other side should go distinctly up, unless something else has created an impact.

LikeLike

weseld1 said

The answer is actually in the video, though not stated clearly. As the Elk population diminished, and the poplars started coming back, the beaver (as the video pointed out) who also eat poplars had a corresponding population growth. So an new balance is being struck, where the limit on poplars is how many beaver they can support, rather than how many elk.

Of course, it is somewhat more complicated, as Elk eat other things that beaver cannot (too far from the water, for example) and there are predators that can eat beaver and not elk, and so on. But this explains how a 60% drop in Elk population will not necessarily cause a 60% (or 6%) rise in poplar population. I don’t suppose anyone has accurate counts of these four species in Yellowstone from say 1900, 1910, 1920 and 1930 to see if there was a reverse cascade of wolves, elk, poplars and beaver back then? I know that 11-years cycles of poplar, rabbits and lynx have been documented in rural Alaska going back for over 100 years, and those cycles were not caused by human interference.

LikeLike

anewcreation said

Surely the general public and those in power should concern ourselves not so much with how Yellowstone is preserved but that it BE preserved. We need to look at the bigger picture if we are to keep this awesome world we live in.

LikeLike

Nordlyst said

I truly don’t understand what your point is.

If we REALLY are concerned, in the proper meaning of the word, about YS being preserved, then necessarily we have to concern ourselves with how!

The entire discussion here revolves around whether or not reintroducing wolves was truly what caused the undoubted revival of the place. It’s hard to see how ignoring such questions – if that is your suggestion – can be construed as “wise”.

LikeLike

trozki said

I agree with you, Nordlyst.

LikeLike

Karen Renfro said

Me, too. Not concerning ourselves with how Yellowstone is preserved is what upset the balance of nature there in the first place. I think the reintroduction of wolves was the effective cause of the natural revival of the park. Mimi posted above that she observed this same process during a lifetime on a ranch. I’m supposing Native Americans and other people who paid attention to their surroundings in past times and present have seen the same thing. I’ve read descriptions of this process in memoirs and articles, but mostly in the form of background noise to the point of the piece. Maybe we should ask around. We might learn something. And we should ask ourselves who benefits if we don’t pursue this question?

LikeLike

Ron Pritchard said

No matter what is said or done in this world, someone will feel compelled to dispute it. There are a vast amount of people who live for dissension.

LikeLike

Richard Hunt said

Most people like things wrapped up into a single cause and effect. The truth is somewhere in between that is not so easily digested. Yes, the wolves were a positive impact on the ecosystem. No, wolves weren’t the only thing that affected the ecosystem. Ecosystems are large and complex and each thing in an ecosystem affects other things and that includes the weather, precipitation, temperatures, over abundance of any one thing can have an impact one way or another. All in all, the reintroduction of wolves was a good thing, they are as natural to Yellowstone as any other species found there. Nature has a way of balance and those ecosystems that are balanced are the best and very stable.

LikeLike

Tom Stevens said

sounds good to me.

LikeLike

Karen Renfro said

True. But, as this story shows, reintroduction of wolves was the single thing that set in motion the other natural forces involved in the restoration, except for things like weather which operate independently of life-forms.

LikeLike

John Counsell said

Remove the Bison Scourge! The uncontrolled overgrazing is what drives Elk and Deer out, not Wolves.

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

Hi John: An estimated 30 to 60 million bison were living in North America in the 1500s. A maximum of 270,000 live here now, almost all on private land. I think the scourge lies elsewhere.

RC

Source: http://www.fws.gov/bisonrange/timeline.htm

LikeLike

weseld1 said

Poor argument Richard: The 30 or 60 million bison living in North America in 1500 were not all living in Yellowstone, but were spread out over half of the continent. The number living in Yellowstone today is very likely higher than it was in 1500. The Yellowstone Bison population is near saturation, as is shown by their constant attempts to migrate out of the nice, protected park, through fences and into places where people will shoot at them. 50,000 deer in my state are no problem; one deer in my garden is a problem.

LikeLike

Karen Renfro said

Good point. Too bad it is immoral for licensed hunters to shoot wild animals even if they are getting out of control.

LikeLike

Karen Renfro said

Aha! Have any of you given thought to how much methane, urea and nitrates all those millions of bison produced during their prominence on the landscape? How did that compare to the beef critters we have now?

LikeLike

Joseph Kissane said

Among the things that impacted the Yellowstone ecosystem in the last part of the 20th Century, the fires of 1988 rank VERY high, but are not considered in the wolf-centered discussions. The gradual reduction in the forest diversity resulted from the continued policy of putting out most fires untilt he 70s altered the ecosystem. That practice also loaded the ground-level of the forest with fuel throughout the park. Coincident with the fire management practices were the dynamic changes in the management of bears – the closing of the dumps and the resulting change in the population and behavior/distribution of bears. Grizzlies are a more formidible predator than wolves, and while they are omnivorous, their impacts are significant. Also, the elk population had reached an unsupportable level – there were over 30,000 elk in the area, and the timing for a collapse in population because of food supply was fast approaching – the fire exploded on the scene, and it happened. Ranchers, the same ones who will howl (sorry for the pun) about hundreds of wolves spilling out of Yellowstone and threatening their livelihoods, were in fits with elk herds competing with their livestock for hay and pasture grazing. Now those same ranchers are whining about wolves killing off the elk they so love to hunt. I spent a lot of time in Yellowstone over the years, and the one thing I learned above all else is that part of its charm is its incredible capacity for the dynamics of nature – change is the biggest constant in Yellowstone. Change in its wildlife, its flora and its geology. They are all linked.

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

Good comment. I flew over Yellowstone in the immediate aftermath of the 1988 fire, also later watched grizzlies killing elk calves there with Steve and Marilyn French. By the way, ranchers are now also whining about wild horses (with reason) and that’s another problem wolves and grizzlies could fix: https://strangebehaviors.wordpress.com/2014/10/01/wild-horses-a-problem-for-ranchers-wolves-could-fix-that/

LikeLike

theredbeardsaga said

Some interesting observations there (well in the actual paper, not just this snippet) – mainly regarding any view that the area might not be salvageable, due to it being ‘too’ destroyed in the first place.

However there is an undue amount of focus on the wolves. Yes the press have focused on them (they’re a ‘charismatic’ species), but rewilding as a whole isn’t just about putting a predator from the top of the trophic system into a degregated area and leaving it be.

It is interesting as well to study the interaction of the wolves with other species, the suggestion that encounters with elk are less intensive than originally thought, is potentially good support for further reintroductions (which is what this was, not necc. rewilding) where too much exposure to such fauna is of concern. However, in other cases the presence of wolves has increased the abundance of flora with berries – which increases the population of bears in the area. This is in addition to the multitudes of papers that confirm wolves influencing prey movement to some extent.

We also are mature enough to regonise that the system must be viewed as a whole: e.g. An increase in willow regen. due to drought, bears, hunters, and wolves reducing elk numbers. Instead of just the impact of the wolves. However this is limited as it still isn’t factoring into account soil, other flora and fauna etc.

Further and finally – the biggest flaw in this retrospective/active analysis, is that the papers aren’t using data collected from pre-wolf introduction.

I would very much like to see what payrolls the author is on, as that is not made transparent. Additionally the subtle levels of scorn from the blogger re: Monboit may tell us all we need to know regarding the ‘re-blogging’ of the paper.

LikeLike

bkswrites said

My problem with the blog post is that it’s 90% or more lifted from the NYT and another writer. I see no indication of permission. Let’s discuss it with the original writer.

LikeLike

Nordlyst said

Could you kindly link to the “original” so people like me can more easily see whether you just made that up?

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

He didn’t make it up. If you look at my post, you will see that I credit the author of the NY Times piece by name, and provide a link. So “lifted” is not the right word. The rules of the game, which used to absolutely preclude re-use without permission, now often encourage it instead, especially in media like the NY Times.

I am ambivalent about this. It routinely happens to me and thus eats away at what used to be a source of income for my writing. But many of the websites and magazines where I write now consider it essential. I’ll check with the author of the original NYT piece and he see how he feels.

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

Here’s the response from Arthur Middleton:

Richard,

Thanks for asking. I am not concerned at all – I think what you have done makes sense and I’m good with it. I like that it gives people further forum to digest and debate the story.

I appreciate the note.

Best,

Arthur

LikeLike

bkswrites said

Actually, to Conniff (and I’m a she, btw): I wish you’d gotten that contact from Middleton 9 months ago. How does the Times feel about it? Crediting the writer and the Times doesn’t go far enough to respect copyright. All of us are at risk of infringement, and especially to the extent that we infringe on or tolerate others’ infringement on the rights of other writers and publications.

LikeLike

Raquel said

like cats are cousins of rabbits but cats are definitely not rabbits =) I like this article. And it bothers me so much when someone comes along to pick it apart!

LikeLike

Nordlyst said

I like it, too. It appears to be a sincere attempt to give tough but fair critique. But as long as “attempts to pick it apart” are equally honest and fair, discussion only makes it more interesting.

To deliberately understate the matter: It is not always the case that blogs and their comment section contain a lot of honest debate. Even the mistakes and misunderstandings and weak arguments are great, in my opinion, because many readers will benefit.

LikeLike

Jon said

It seems that what is missing is an understanding that the ecosystem was profoundly damaged by the loss of many meso and megafauna from these environments only looking at the precolumbian ecosystems not human introduction to the Americas. The horses are a critical part of reestablishing a normal ecosystem here. Horses are native to North America until their extermination by the paleoindians and their return will help these systems.

LikeLike

Chuckk said

I know this is a minor point, but the badger shown in the video is a Eurasian badger, which has never existed anywhere near Yellowstone. Look it up. You can call me petty, but I’m still right…

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

Not minor at all. It happens all the time (and drives me nuts) that editors in film or online think, oh, it’s a story about a monkey species, so I can use any monkey picture I come across. I’ve sometimes done the equivalent by mistake, but try to fix it when people like you point out my error. This wasn’t my video, but thank you.

LikeLike

Julie said

What’s getting lost in this thread is that the wolves don’t control by killing alone – they keep the herds on the move. It’s when the herds stagnate in place that they do the most damage. And it has been shown that overall elk populations are basically stable in the last decade. It’s just that the elk are moving around more. Meaning that hunters no longer have the luxury of shooting elk from their vehicle windows or back porches.

LikeLike

Duane Short said

Nobody’s right when everybody’s wrong. We have left nature as a baseline from which to perceive the natural processes around us. Until we accept nature as it has evolved (and, by the way, is still evolving) our opinions, no matter how seemingly astute, are drivel. Until we stop trying to conquer nature and put the whole of it in a box we call man-age-ment we kid ourselves and mislead those we try to persuade. Nature and the discipline of ecology are very complex topics. At the point we think we know enough to man-age nature, is the point at which we have derailed, each becoming a car in a train-wreck 7 billion human beings long, spilling our cargo of dogma, entrenched ideas, arrogant convictions, and science that is often exaggerated as much as the trout that got away or buried as deep as the wolf falling victim to the shoot-shovel and shut up culture that permeates its historic range. For a human being to think and act “naturally” is heresy in this “control freak” civilization we have unwittingly created for ourselves. We are now the top predator, but should we be?

LikeLike

Nordlyst said

A great appeal that will resonate with all who don’t like to think too much.

What you call “putting nature in a box” is basically the same thing that we might also call “our industrialized world”, “the economy”, and “food Production”. It may seem a romantic prospect to just give up on all that and rewind to a time when Man did not so greatly impact his environment, but we better realize this is a virtual, if not a physical, impossibility. There are already far too many people!

Maybe everything really was better before (since however much better they may be right now, they don’t seem possible to sustain at all). Perhaps we shouldn’t have painted ourselves into this corner.

But we have. We better figure out how to deal with it. I’d like to know what YOU propose we do about it. Nuke most people to bring the numbers down to a more sustainable few hundred million? Make it illegal to have children and issue licenses to just a few to achieve the same more slowly and without killing anyone? Something entirely different? I’m all ears. I’d love to hear HOW we should do this as well, for instance if the majority of the public disagrees. Find a benevolent dictator? Again, how?

I for one think we are in a position where our only chance to avoid life getting worse for people, rather than go on improving as it has, is to radically up our game and start investing seriously in science. The fact that our knowledge is so incomplete is a huge problem. But the fact that we spend less than one percent of our resources on advancing our understanding means we probably can accellerate our learning quite considerably.

If we focus on feelings of indignation, however understandable they may be, the future will be worse for a lot of folks than if we face the challenge and do our best to tackle it. I think the first thing that needs to happen is we need to accept that right now, economic growth is nowhere near the most important thing to concern ourselves with. If the day ever comes around when we have learned how to grow sustainably, hurrah and let’s bring growth back on the agenda. In the meantime, it ought to be obvious that growth is at the core of the problem. Still, every industrialized nation on the planet has as its de-facto primary goal to increase “wealth”, despite knowing this may seriously undermine everyone’s chance to experience any kind of wealth for decades or even centuries to come! (Who knows; let’s throw in “forever”!)

In short, I think I share your sentiment, but what we need is its polar opposite.

LikeLike

Bob Koorse said

Well said. We have what we have. Second guessing the mistakes that have been made is only useful if it helps us avoid similar mistakes. Time to be smart. Understand the priorities. Control as best we can the complications. Getting the bulk of humanity on board to set priorities is the real bear here. That “economic growth thing.” That’s like the tumor that keeps growing.

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

For an approach that’s very different from the introduction of wolves in Yellowstone, and far more successful, this might also be worth a read: https://strangebehaviors.wordpress.com/2014/12/18/wolves-and-bears-make-comeback-in-crowded-urban-europe/

LikeLike

Don R. Helms said

Life is complicated. Simple solutions have one thing in common. They are all wrong! By the way, I was studying at Purdue back in the ’50s’ when Dave M. started his PHD under Dr. Durward Allen on moose/wolf relationships on Isl in Lake Superior. The proposed balance between wolf and moose was a big thing then – us gullible students ate it up. There is no balance, it is a dynamic moving agenda of nature.

LikeLike

TEA & TWO SLICES | On The Hottest Year On Record And Hipsters With Craft Beer Bellies | Scout Magazine said

[…] And this: Maybe Wolves Don’t Change Rivers, After All. […]

LikeLike

Kirk said

I was skeptical about this article until I got to the place where the author mention the warmest climate in 6,000years. Then I knew the guy was full of BS and writing to hear himself. Also, there is nothing man can do that nature can not undo, given the opportunity.

LikeLike

Los lobos cambiaron los ríos | Reveración said

[…] La cascada trófica es una descripción de los efectos interrelacionados que un depredador principal tiene sobre el ecosistema en el cual vive [1]. Por ejemplo, cuando el lobo gris fue eliminado del Parque Nacional de Yellowstone, la población de ciervos aumentó y este aumento llevó a la disminución de plantas que el venado comía. Hay un entretenido video en YouTube titulado “Como los lobos cambiaron los ríos” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nHdBB9zTuNA el cual menciona cerca de nueve efectos que produjo la reintroducción de los lobos a Yellowstone. Antes de emocionarse demasiado con este video es importante leer el artículo “Maybe Wolves Don’t Change Rivers, After All,” (“Después de todo, quizás los lobos no cambian los ríos”) (https://strangebehaviors.wordpress.com/2014/03/10/maybe-wolves-dont-change-rivers-after-all/). […]

LikeLike

dw said

Stop gripping about the wolf killing deer. They were here long before we were. The same as the American Indians. Seems we didn’t have a problem killing them off when they got in our way. Cry to someone else when a coyote kills your Chihuahua. Keep building houses, shopping centers and every other materialistic thing that you want and keep minimizing the area that the natural animals have to live in and there will be consequences.

LikeLike

Tuesday, November 24: How Wolves Change Rivers | Science 6 at FMS said

[…] Maybe Wolves Don’t Change Rivers, After all– https://strangebehaviors.wordpress.com/2014/03/10/maybe-wolves-dont-change-rivers-after-all/ […]

LikeLike

Eilish said

This article provides no sciencetific proof. You can’t just repeatedly say a fact observed by scientists is untrue without providing any evidence.

LikeLike

Barry McPhail said

This discussion….and the source articles….are classic examples of science as discussed by non-scientists. The media and the public they serve like a simple, well-told story: the truth is more complex. So first we have story A: wolves have a significant effect on the Yellowstone ecosystem….public goes “Yay! Wolves good!” then we have story B: it’s more complicated than that…..public goes “Story A is crap!”

Along with rabbit trails on the difference between deer and elks in a popularizing video (a tertiary source at best) and even a foray straight down the rabbit hole itself about climate change.

The actual truth of the matter is probably more complex and will be parsed out in the pages of Nature, Ecological Monographs and other such publications. Simplistically though: the wolves had a profound effect on the community structure of Yellowstone but not the only effect and not at all times and places unambiguous.

So I suppose in the end, I’m coming down simplistically myself: Wolves Good…..but that’s not the whole story.

Baz

LikeLike

Barry McPhail said

My $0.02:

I have no actual data, since I didn’t have the presence of mind to collect it at the time, but anecdotally I’ve seen a striking case of the effect that wolves can have on the grazing behavior of herbivorous prey and the resulting secondary effects on the vegetation.

In the early 90’s, I was involved in a census of vegetation on the offshore islands of Mississippi as a contractor for the NPS. The islands are about a mile wide and vary in length from 3 to 13 miles. The shores are lined with sand dunes and the interiors are freshwater marshes. The nutria population on the islands was having a severe impact on the sea oats which are the predominant grass holding the primary dunes intact. Typically, on all of the islands but one, I would see three to five or more little potholes where nutria had dug up the grasses’ rhizomes for every intact stem of the sea oats. On the last, largest island (Horn Island) at the time, the NPS was raising a single family of radio-tagged red wolves on the island as a source of wild-born cubs to re-establish wolf populations elsewhere in the South. Walking the dunes in the morning I would see multiple wolf tracks where they ranged up and down the beach during the night. The difference was amazing and obvious. On Horn Island, there were no evident grazing potholes and the density of the sea oats was greater by a factor of five to ten in my estimation. A single group of wolves of five or six could not possibly have constituted a predatory control on a population of nutria on an island of 12-15 square miles. Nor can I imagine another factor which might have effected this change on Horn Island and not on the other islands of the chain. The obvious conclusion is that the wolves were affecting the nutrias’ behavior and causing them to mostly confine their foraging to the interior marshes.

As I said, I’ve got no real data, merely educated observations, and no follow-up, so the effect may have been short term or due to interactions I am not taking into account….but it’s a pretty strong and compelling story to me.

LikeLike

marie said

Maybe this biologist is the mouthpiece paid of the ranchers and anti wolf corporations and trapper associations. He is elk-lover and wolf hater himself.

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

Hang on there. If he were being paid he would be obliged to declare a conflict of interest in any publication. Also this isn’t an anti-wolf story. It’s simply an attempt to show that nature works in far more complex ways than our stories tend to acknowledge.

LikeLike

fernando vazquez said

Marie it is not a simple attempt of nature it is

LikeLike

Albert Head said

Lord save us from the armchair critic. Had the video never been made, the cold and timid soul (to quote Roosevelt) would never have had his day.

LikeLike

cyclohexanone2002 said

What a load of old nonsense. The writer of this article seems to be quibbling over a few minor details, mainly the Aspen regrowth as well as the fact that he puts the fall of the elk population, not just down to the wolves, but down to human hunting and bears. Well for one thing, humans have always presumably hunted and the reintroduction of the wolves wouldn’t have any change on human hunting. He also cites bears? Well of course bears hunt the elk, but bears and elk had been living side by side for a number of years before the wolves were introduced, and how he has the gall to say that the wolves are not directly responsible for the decline are beyond me.

To me, it seems like he is a nobody scientist, just trying to make a name for himself.

LikeLike

Paul said

On June 15th 2016 the House Committee on Natural Resources held a legislative markup on 19 bills and passed two out of committee that would spell disaster for our national public lands.

Rep. Raul Labrador’s (ID) Self-Sufficient Community Lands Act (H.R. 2316) and Rep. Don Young’s (AK) State National Forest Management Act of 2015 (H.R. 3650) would result in the seizure of millions of acres of public lands and threaten the health of our national forest system, fish and wildlife habitat, and public access to quality hunting and fishing.

Contact your members of Congress today and tell them legislation like this doesn’t belong in America – and would compromise the integrity of our proud public lands legacy.

LikeLike

Anna said

I’m sorry, but a two year study really doesn’t convince me. Like you asked, does it matter if it’s true or not? Of course not. I’ve grown up in the wilderness, and I’ve spent a lot more than a couple of years observing wildlife. It only takes one animal in an surprisingly large area to have an impact. All you have to do is look around and see this. You scientists are a funny bunch. I’m sure your particular group of elk were safer from the predators and in turn probably didn’t see much of a difference. However, following around one herd of elk for a couple of years really isn’t enough proof to deem the former findings false. This, and the fact that the changes where already in place when your study began (forgive me if my presumptions are incorrect) tell me that your findings are questionable.

LikeLike

The Impact of Wolves – Critical Kittens said

[…] Then follow up by reading this article. […]

LikeLike

Steven Burkhardt said

It is clear to me that the author doesn’t understand forest succession, and not much about wildlife behavior. Of course aspen are not going to suddenly appear, outgrow, and crowd out lodgepole pine. That isn’t how it works. Studies have shown that excluding large ungulates from a natural setting has profound effects. I visited one such study area in Rocky Mountain NP. A elk exclosure has been set up to study the effects. The amount of undergrowth coming up is staggering, including aspen. The most common method of their propagation are suckers that pop up after forest overstory is removed, such as a forest fire. Critters then eat this new growth. I earned a degree in forestry, concentration in forest fire science. At Colorado State’s mountain campus I studied this in a natural lab, 3 years before I attended the natural resource summer session campus there was a forest fire that included a part of this campus. I was also a park ranger on Isle Royale National Park, where the longest wolf/prey study has been going on. The presence of wolves do indeed change prey behavior, changing the movement patterns. This will have an effect on undergrowth and the amount of biomass in a location that is no longer frequented by large herbivores. Yes aspen will take off, but it will be replaced by lodgepole. Just as the Yellowstone fire in 88 removed the overstory, allowing aspen, grasses, and forbes to thrive, it was all replaced by the slower growing lodgepole. What I am getting at is modify/change any part of the web of life in an ecosystem there will be an effect elsewhere within that web. And this is illustrated by the reintroduction of wolves to the changes they made, which led to actual changes in the landscape. The author needs to get out of the city and back into an actual natural environment

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

UPDATE: In most European countries there are now permanent, reproducing populations of wolves, lynx and/or brown bears. In some countries, all three. But it is not virgin land that these animals recolonize, but rather lands that are characterized by high human activity.

In a review article in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B a European research group highlights gaps in knowledge on the effects of carnivores in human-dominated landscapes.

“There is a widespread perception that the return of large predators will save biodiversity,” says Joris Cromsigt, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), who is one of the authors. This view is partly based on experiences from Yellowstone National Park. When wolves were reintroduced in this national park, grazing pressure was reduced on the vegetation along the watercourses, which in turn led to a richer flora and fauna. “However, in Europe predators are now returning to landscapes that are strongly modified by humans. Man is part of these ecosystems. Although we are not always physically present, these landscapes are still heavily shaped by us, for example, through forestry and hunting.”

The ecological impact of large carnivores will most likely be quite different in these anthropogenic landscapes. The review that the authors put together suggests that several of these human actions may mitigate the top-down effects of large carnivores. In other words, humans may remove the claws from the carnivores’ paws. Perhaps even more important is that the authors suggest that most of the research done so far on the role that predators play in ecosystems has been carried out in landscapes with very low human impact.

“Human activity must be included in research on the ecological effects of large carnivores. This article emphasizes that there are many unexpected ways how humans affect the role of large carnivores in ecosystems,” says Cromsigt.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU). Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:

D. P. J. Kuijper, E. Sahlén, B. Elmhagen, S. Chamaillé-Jammes, H. Sand, K. Lone, J. P. G. M. Cromsigt. Paws without claws? Ecological effects of large carnivores in anthropogenic landscapes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2016; 283 (1841): 20161625 DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2016.1625

LikeLike

zoransulc said

I’m disappointed that the original video paints a too idealistic picture – it really is an inspirational piece of work. So, my question is, Did George Monbiot believe what he was saying in his video, or did he know it wasn’t quite true but, knowing what the masses needed to hear and what was good for us, he told it anyway?

LikeLike

Chris Smith said