Trophy Fish–And A Chain of Species Destruction at Yellowstone

Posted by Richard Conniff on May 14, 2019

by Richard Conniff/The New York Times

Recreational fishing is a pastime in which people have come to expect the fish they want in the places they happen to want them. That is, they want their fish stocked and ready to catch, even in places those fish never originally lived. This practice can seem harmless, or even beneficial. But the introduction of one “beneficial” species in Yellowstone National Park suggests how rejiggering the natural world for human convenience can cause ecological disaster for almost everything else.

All it took at Yellowstone Lake, the 136-square-mile centerpiece of the park, was the introduction of lake trout, a fish originally found mainly in the Northeast and Canada and beloved by anglers everywhere. The federal government had transplanted them to smaller lakes within the park in the 1890s, a time when adding fish to remote fishless lakes seemed like a smart way to spread around America’s amazing abundance. But a century later, in 1994, the introduced species turned up in Yellowstone Lake, which was already celebrated for its own native Yellowstone cutthroat trout. Park managers theorized that an angler illegally introduced the fish, either by accident or in the misguided belief that it would improve a big lake with plenty of potential for further sportfishing. One result is that anglers now catch 20,000 lake trout a year there.

But the lake trout went on to gorge on the young of the cutthroat trout, and the population of the native subspecies plummeted. Because there were fewer cutthroat trout around to eat them, large water fleas soon proliferated. The water fleas in turn gobbled up the microscopic plants at the bottom of the food web, causing the lake water to become clearer and probably also warmer near the surface, according to a new study published in the journal Science Advances. When the cutthroat trout largely vanished from the shallow waters they prefer, the lake trout didn’t take their place, because they like deeper waters. So the switch deprived ospreys, white pelicans, bald eagles and other fish-eating birds of their main food source. The osprey population around the lake soon dropped from 38 nesting pairs, with almost 60 percent of them successfully fledging young birds, to just three nests with zero success. Eagles likewise declined almost to a level last seen during the height of DDT use in the 1960s, again with zero reproductive success.

Because far fewer cutthroat trout were making their springtime spawning run up streams around the lake, grizzly and black bears that once lined the banks to feed on them had to go elsewhere in search of food. The density of river otters also fell to the lowest levels known for that species. To casual park visitors the lake no doubt still looked wild and beautiful (that clear water!). But it was like visiting a celebrated European city when all the locals have vanished and everybody you bump into is a tourist.

What happened at Yellowstone Lake is a familiar story for conservationists, because fish stocking has produced cascading ecological disasters pretty much everywhere. For this, Americans can thank Robert B. Roosevelt, a 19th century congressman, conservationist, and uncle of Theodore Roosevelt. He was the fishing world’s version of the infamous New Yorker who set out to give his fellow Americans every bird mentioned in Shakespeare and instead bequeathed us a plague of starlings.

Roosevelt was a leading proponent of the post-Civil War “fish culture movement,” which espoused hatchery-reared fish as a means of replenishing depleted stocks of native species. But Roosevelt also promoted hatcheries as a tool for swapping species willy-nilly across the continent and the globe, with fish eggs shipped “from one end of our country to the other with as little trouble or danger” as a letter dropped in the mail. “Rivers that are now deserted could be filled to repletion,” Roosevelt gushed, “so that there would be abundance for netters, seiners, and fishermen of all kinds, whether they fished in season or out of season, early or late, and with murderous or legitimate implements. This is the object to be obtained.”

In 1871, Congress established the United States Fish Commission, the first federal agency set up to address the depletion of a natural resource. Roosevelt ensured that the legislation included a mandate to move fish into new territories. “There is no reason why the waters of the West should be less prolific than those of the East,” he argued, “provided the right species were introduced; and were trout, salmon, bass, shad and sturgeon to take the place of catfish, pickerel and suckers, the gain would be manifest.”

So what can we do about it now? The spectacle of a pristine ecosystem being wrecked almost overnight forced Yellowstone to undertake a major effort to remove lake trout, according to Todd Koel, who heads the park’s native fish conservation program. As a result, the cutthroat trout population is slowly recovering and the spawning run in nearby streams is rebuilding. But the control program costs taxpayers and donors $2 million a year and will continue to do so, says Dr. Koel, “for the foreseeable future.”

A better plan is of course to prevent these introductions from happening in the first place. Some anglers now recognize the threat and work to educate other anglers about how doing things that may seem beneficial or even humane — dumping a bucket of live bait at the end of the day, or releasing unwanted fish from one lake into another — can wreck the fishing for everybody else. Some jurisdictions have also begun to enlist anglers in the control effort, by removing bag limits or banning catch-and-release for problem species. At Yellowstone Lake, the rules announce in bold face and italics that lake trout “must be killed — it is illegal to release them alive.”

State and federal agencies have refrained in recent decades from stocking nonnative species into new territories. Some agencies have also begun to designate native species conservation areas, removing barriers to upstream spawning areas and maintaining barriers against downstream intruders. But the practice of stocking nonnative fish into water bodies where they already exist remains standard for now, because the people who pay fishing license fees want it and an entire recreational fishing industry depends on it. The theory, in any case, is that the damage is already done — though that may prove to be wishful thinking, as increased flooding causes introduced species to spread to new habitats, and to still other new habitats beyond that.

A Saturday morning spent fishing is at least still an opportunity to get outdoors and enjoy what nature remains to us — and maybe even forget for a little while the recent news about the extinction emergency now threatening a million or more species worldwide. But for an angler standing by a stream and casting out a line, the thought that rises helplessly to mind is that every species we lose, every habitat we compromise in the name of “human convenience,” is one more piece of the American character and of our own souls inadvertently washed away into oblivion.

##

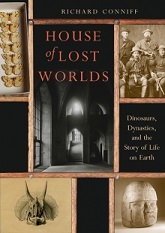

Richard Conniff is an award-winning science writer. His books include The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth (W. W. Norton, 2011). He is now at work on a book about the fight against epidemic disease. Please consider becoming a supporter of this work. Click here to learn how.

Jack said

Awesome article something to think about

LikeLike