Big, Bad & Very, Very Toothy: A Shark’s Tale

Posted by Richard Conniff on February 13, 2024

Tim Flannery was first bedazzled by megalodon teeth as a “mad-keen” teenage fossil hunter diving in the shallow coastal waters off suburban Melbourne. Of one prized find, he writes that “its enamel was lustrous, glossy green in colour, and as I floated in the sunny water above it shone from its bed of sand with an uncanny brilliance . . . like an expensive necklace in a jeweler’s window.” In his subsequent career, he went on to other things, earning renown as a paleontologist, a mammalogist, a climate activist and an author. But the teeth still clearly hold him in their powerful grip.

Using the modern great white shark’s teeth to put megalodon’s choppers in context would be, the Flannerys write, “like comparing a toothpick to a pickaxe.” The largest megalodon tooth ever found is 7.5 inches long, and a single tooth can weigh more than 3 pounds. They theorize that our human and prehuman ancestors have been collecting them for eons, for some of our earliest tools, ornaments and magic charms.

According to the Flannerys, collectors “infected with the fossil fever” continue to get stuck on megalodon teeth today, and not just metaphorically. In central Florida’s Bone Valley, collectors risk “the peril of errant trucks” while out searching for fossil teeth in mine tailings used as road covering, or they stand hip-deep for hours in cold water “shoveling gravelly sludge they call ‘gravioli’ into sifters, hoping to find ‘the big one.’ ” Some of them are “so obsessed with this activity that they’ve worn their hips out as they agitate their sieves, and have had to have them surgically replaced.”

Most of megalodon’s modern-day kills are divers, particularly the ones who work the “deep, dark and deadly holes” of the American Southeast. The Flannerys describe one expert collector they call the “Don of Megalodons,” who filled a bag with shark teeth on a 2004 dive in the turbulent, tannin-blackened waters of Georgia’s Ogeechee River. He never managed to bring it to the surface. The authors speculate that the thrill of collecting may have led him to miss the warning signs of nitrogen narcosis. “Perhaps in his delirium he imagined that he was picking the teeth from the maw of the great shark itself.” But the river had plenty of other ways to kill him. It took the rescue team a week to find and recover the body.

All this makes for compelling reading. Fussy readers may question whether megalodon was indeed the largest predator, a claim that appears on the cover and throughout the book. The authors themselves acknowledge that megalodon was only half the size of the modern blue whale, and blue whales are definitely predators, if not generally scary ones for us.

Readers may also sense a missed opportunity. The narrative is largely Tim’s and told in the first person. When Emma eventually makes an appearance, late in the book, it is Tim telling a third-person story about how viewing the movie “Jaws” with neighborhood children as a 6-year-old left Emma traumatized. Now in her 30s, “she still suffers from recurring dreams in which a giant shark lunges out of the shadows and encloses her in its jaws.”

This might well have been a fine background for diving into the psychology of our fascination with sharks. It could have been the beginning of a dialogue between the nightmare-prone daughter and the father who used to dream about “walking over beaches paved with perfect megalodon teeth.” Just imagine. Sadly, we never get to hear Emma speak in what feels like her own voice.

##

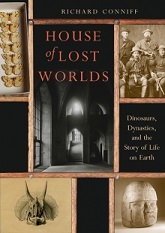

Mr. Conniff’s books include “The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth” and “Swimming With Piranhas at Feeding Time: My Life Doing Dumb Stuff With Animals.”

Pages: 1 2

Leave a comment