Genealogy Is Bunk

Posted by Richard Conniff on July 1, 2007

UPDATE: I know a lot of you diehard genealogists think this article is bunk. So good news! It now appears that at least one part is indeed bunk. Scientists have gone back to test the idea that in 10 percent of births, the real dad is somebody other than the guy on the birth certificate. When they tested more rigorously, that number dropped to just one percent of births. Check out the article by @CarlZimmer in The New York Times. Now, you newly empowered (but still misguided) genealogist, read my original Smithsonian Magazine article, “Genealogy is Bunk”:

by Richard Conniff

Go back just 10 generations, to about 1750, and in theory I have more than 1,000 direct ancestors. Back 20 generations, the number climbs to well over a million. If I look to my presumed descendants in future generations, the numbers are equally daunting. Either way, how much should I care? Growing up in a family of six kids, I often had trouble keeping track of my own siblings. The idea of 1,000 ancestors leaves me paralytic.

Until recently, hardly anybody kept close track of their ancestry. They were too busy picking lice out or their hair or fending off the Black Death. Detailed record-keeping didn’t exist, nor did the family names we now take for granted as the key to genealogy. (Surnames started to turn up around the 14th century in Europe, and not until the 19th century in some parts of the world.) Instead of obsessively trying to link themselves to social betters in the distant past, people were basically stuck with the five generations immediately around them, meaning grandparents, parents, siblings, children and grandchildren. And unlike the lofty souls we strode among in days of yore, the people we live with in the here and now have a dismaying knack for reminding us of our humble origins. To a former boarder with social pretensions, my great-grandmother once remarked, “I wouldn’t take ye back if yer arse were made of diamonds.” No descendants of Charlemagne need apply.

It’s different now. People have become consumed with genealogy, which is a $1 billion industry in this country. According to surveys, roughly half of all American families have constructed a family tree. And when they hit pay dirt, the results often become a claim on the public attention: bald-headed singer/songwriter Moby takes his stage name from the great white whale in his distant relative Herman Melville’s best-known novel. Playboy founder Hugh Hefner boasts that he is an 11th-generation descendant of a Mayflower Puritan. Author Joan Didion’s great-great-great-grandmother rode with the Donner Party. And Paris Hilton gets her first name from an ancestor who was the preening twit in The Iliad. (Okay, just kidding about that one.)

Genealogy became a subject of popular fascination after Roots, the 1970s book and television mini-series in which writer Alex Haley traced his ancestry back to an 18th-century warrior in the African nation of Gambia. Like many genealogies, this one turned out to be fictitious (and partly plagiarized). Regardless, Americans proved highly susceptible to genealogy’s lure. Maybe it’s because we live in such a mobile society, often separated from family by thousands of miles. Many African Americans, in particular, feel cut off from their heritage by the slave trade. Conjuring up a family tree and figuring out where we sit in it gives us back a sense of place, of connectedness. Throw computers, Internet databases and DNA into the mix, and this compelling hobby can become an obsession.

My daughter dotes on a web site called geni.com, which enables her to put genealogical information online and connect with information about distant, unsuspected relations. Or even not so distant. I discovered three first cousins I’d never met, though we all grew up in New Jersey. My elder son enjoyed dinner with a first cousin once removed he found living near him in Seattle. (He knows precisely how they are related because geni.com told him—probably an improvement on my catch-all term “dog kin.”)

All this sounds harmless enough. But people intent on using DNA to make such connections now venture out to “swab the cheeks of strangers and pluck hairs from corpses,” according to a recent article in the New York Times. One 63-year-old “wastewater coordinator” and amateur genealogy sleuth staked out a McDonald’s so she could covertly lift DNA from the coffee cup of “the last male descendant of her great-great-great grandfather’s brother,” who quite reasonably regarded his DNA as none of her business.

Doesn’t it make you wonder if we shouldn’t think through this genealogy thing a bit more clearly? There are more potholes and mudslides on this road than most of us care to admit.

Let’s start with the genealogical follies of the rich and famous. They used to be the only ones who bothered with family history. It was a way to maintain their power, by asserting that they’d always been here and therefore always would be. Curiously, biologists doing long-term studies of primates in the wild say that’s how family connections function in nature, too: in high-ranking baboon and vervet monkey families, grandmothers routinely make sure that little Tiffany Baboon and young Percy Vervet III get special treatment from lesser juveniles. This gives the kids a habit of social dominance—and can thus help maintain a monkey dynasty for generations.

A lengthy pedigree is so useful that human families have often found it convenient to invent one. When a British family ascended in the 17th century from being mere Feildings to being Earls of Denbigh, for instance, they revealed the happy news that they were in fact kin to the Hapsburg emperors. In India, royal families employed genealogists to recite the family history, in one case going back 450 generations. That would be around the end of the last Ice Age and well before the birth of civilization itself.

Who were they kidding? Social scientists conservatively estimate that “misassigned” paternity occurs in about 10 percent of all human births. That means Daddy isn’t always the guy listed in the official records. We’re not just talking Anna Nicole Smith here, or segregationist Sen. Strom Thurmond, who secretly fathered a child by his family’s black housekeeper. Go back 10 generations in any family, and the odds are that someone has climbed unacknowledged up the family tree. Sir Winston Churchill prided himself on his descent from the great 18th-century general John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough. But the family had a colorful history of sexual misadventure; Winston’s own father died of syphilis, and his mother was said to have taken 200 lovers during the course of their marriage. Likewise, Hugh Hefner would doubtless admit that even Pilgrims sometimes fooled around. So genealogical skepticism is always prudent. The corollary is that many humble souls born in the immediate vicinity of great families can probably make just as good a claim for a place in the family hierarchy. In fact, a group called the Descendants of the Illegitimate Sons and Daughters of British Kings does just that. You can look them up at royalbastards.org.

But let’s say your ancestors were saints, and your pedigree happens to be immaculate. How closely can you connect yourself to that scientific genius, that noted author, that fighter for his people’s freedom? The simple mathematics of division by two in each generation would suggest that, after nine generations, Winston Churchill would possess no more than 1/528 of his famous ancestor’s DNA—and DNA inheritance isn’t nearly that simple. At conception, half the mother’s DNA and half the father’s go into each of the child’s 23 chromosome pairs. But there’s no telling how much of their DNA will make the more or less random cut when their grandchildren are conceived, or in any of the subdivisions after that. The bottom line is that you may possess no genetic connection whatsoever to your own great-great-great-grandfather.

So what’s a better way to think about genealogy? The temptation is to pay attention only to the good news, and look on the family lineage as a golden thread leading from some glorious ancestor straight down to the lucky modern-day descendants. But no family lineage is just one thread. It’s more like a broad fan of a thousand, or a million, threads coming together from all over the world to weave the fragile patch of material representing the generations of family immediately around us.

And here’s the curious thing about this ancestral fan: It doesn’t follow the simple mathematical rule of doubling with each generation back into the past. If it did, we would have between four billion and 17 billion ancestors at the time of Charlemagne in 800 A.D., when there were only a few hundred million people alive on Earth. Instead, because of intermarriage, the same ancestors start turning up in any lineage over and over. Thus Edward III, king of England from 1327 to 1377, appears 2,000 times in the family tree of the modern-day Prince Charles, and he would probably occupy an additional 12,000 spots if the full genealogy were known, according to Robert C. Gunderson, a professional genealogist who has studied the British royal family. Royal families are a special case, of course, because they used inbreeding to keep the wealth and power within a limited family group. But virtually all families practiced some degree of inbreeding, often without realizing it. It was a natural byproduct of marrying people who lived within walking distance.

So common ancestors start to turn up even in families who might appear to be completely separate. In the 2004 U.S. presidential election, for instance, genealogists traced both George W. Bush and John Kerry back to the same couple living in the Plymouth Colony in the 17th century. Big deal. Almost everyone reading this article has Julius Caesar as a common ancestor. Half of you can probably claim Charlemagne, too. That’s because they lived a long time ago and went about the business of forefathering con gusto. You are probably also descended from every sniveling peasant who ever managed to replicate in ancient times.

The idea of our common ancestry is hardly new. That’s what the story of Adam and Eve was all about. Even so, a lot of people were surprised in the 1990s when genetic analysis determined that we are all descended from a “mitochondrial Eve” who lived in Africa just 100,000 to 200,000 years ago. But that study looked only at the mitochondrial DNA, which gets passed from mother to daughter. That got other scientists wondering what they’d find if they looked at genealogy rather than genetics. And when they calculated the overlapping ancestry in both the maternal and paternal lines, they concluded that everyone on Earth today shares a common ancestor who lived just 2,000 to 3,500 years ago. Because that ancestor’s parents and grandparents were naturally also common ancestors, our genealogy starts to look increasingly similar with each generation back in time. It’s not just that we have one common ancestor, but by the time you get back 5,000 to 7,000 years ago, all our ancestors are the same. At that point, says Yale statistics professor Joseph T. Chang, “everybody is either a common ancestor of all people alive today, or of nobody alive today.” Or as he and his co-authors put it in an article in Nature, “No matter what languages we speak or the colour of our skin, we share ancestors who planted rice on the banks of the Yangtze, who first domesticated horses on the steppes of the Ukraine, who hunted giant sloths in the forests of North and South America, and who laboured to build the Great Pyramid of Khufu.” Our genealogy is, in a word, identical.

So am I going to tell my daughter to lay off geni.com and forget about the family photos? Probably not; she is a teenager and has a terrible scowl. In any case, there isn’t much satisfaction in the idea that we are all basically the same, all just part of the grand, bland Family of Man. What makes families interesting isn’t the 99.9 percent of things we have in common, but that quirky extra bit that makes us different. I’d like to know a little more, for instance, about the origins of our family name, which means “son of a black hound” in the Irish language. And I am deeply curious about my Italian great-grandfather, who used to chase my father down Webster Avenue in the Bronx swinging a sickle and yelling, “I catch-a you, I keel-a you.” These are the small, sweet pleasures of family history.

But I also want my daughter to understand that nothing in her genealogy defines her. Our ancestors are dead, and they should let us rest in peace. What makes us who we are, what makes us people worth knowing, comes from within ourselves, and from the often annoying, somewhat laughable, occasionally lovable families we live with now.

rconniff said

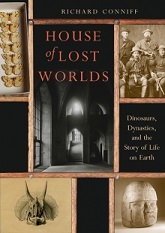

I wrote this story for the July issue of Smithsonian Magazine. It has stirred up lots of controversy, and even inspired a line of products bearing the angry motto, “Genealogy is not bunk.” So I thought I ought to post it here for readers who might not have access to the magazine.

LikeLike

attachment parentingideasgift ideas said

attachment parentingideasgift ideas…

[…]Genealogy Is Bunk « strange behaviors[…]…

LikeLike

mike2211 said

test

LikeLike

mike2211 said

This is such an important article, thanks for posting it. (I read when originally published in Smithsonian and was glad to find online 5 years later.) 3 comments:

1. I first learned of the “10% rule” – that DNA tests have revealed approximately 10% of the time someone we think is our biological parent (usually father) isn’t, due to infidelity or unrevealed (to child) adoption, which would completely invalidate that branch of the family tree – in Jared Diamond’s “The Third Ape.” This needs to be more publicized, because people claiming some famous ancestry from many generations ago can never be certain although they certainly feel they are. And like the article says, everybody else probably has that same ancestor.

2. The analogy of a small bush branching out to many descendants rather than a tree descending to one is much more apt.

3. I showed this article to an adopted friend who will never know who her biological parents are and she appreciated it.

LikeLike

dell said

I agree with all you say. I used to be a keen genealogist and woke up.

As you say, we are the sum of our life experiences.

Dont you think Genealogy is a negative hobby? I found myself constantly dwelling in the past etc. When I should have been living in the now.

LikeLike

Susan Nash said

You’re assuming a certain set of values for genealogist that don’t exist. Most genealogists aren’t just interested in famous ancestors. It isn’t about being snobby about who we are based on who we came from. For me it is a way of understanding history in an intimate way. History comes alive in the struggles of our ancestors to survive. Once you go back 200 years there’s not much in the way of details. Just because you don’t understand what is interesting about ancestors and their lives doesn’t mean that it isn’t interesting.

The sense of belonging or ownership you get from reading about an ancestors life motivates you to learn about things you might otherwise not bother with. I had an ancestor in the Army who collected fossils during his time guarding the railway builders from Indians. He later helped found a natural history museum in San Diego. (I had a fascination with archeology as a child) His grandfather was a son of a well off French family who paid for a replacement soldier to keep their son out of the Napolean Army. He later was a professor of French at West Point. My dad probably consulted books in the library put in place by his ancestor during his 4 years at West Point. (my dad used to solve crossword puzzles in French and German!) My dad and I meanwhile are very word friendly techie nerds. I feel connected to events that make the world the way it is now. The dirt poor Indiana soldier tramping across the country during the Civil war is another of my ancestors who helped me experience that in a more personal way than the typical dry history lessons full of dates and names. (I don’t necessarily think any of those things were handed down via DNA.)

Don’t disparage something you don’t understand based on superficial observations or the behaviors of a few.

LikeLike

Kat said

I wanted to reply, but you said it all, and better than could I.

Thanks

LikeLike

Mark said

It’s unclear if Julius Caesar has any surviving descendants, actually. Augustus is much more likely.

For me, genealogy is just about situating myself. Sure you reach the Identical Ancestors point, and sure there is questionable paternity (one reason DNA is a neat tool), but for me it’s basically about how far I can make a chain in the records.

My ancestors were all peasants and every line dead-ends around the mid-1700s. But so what! It’s made the last 250 years a lot “smaller” and the World a lot smaller too, in simply just learning that the task was possible (I used to think my immigrant ancestors crossing the ocean in the mid-to-late-19th century was a “fog of time” situation permanently cutting me off from my roots. Not so! I’ve found the ancestral villages in Europe for all of them).

LikeLike

genie ologist said

Actually most highly dedicated genealogists that have spent years building the charts of highly documented royal and noble families of Europe will be able to show you that 90% of the descendant line branchings from any royal couple 600 years ago are now extinct.

However of the few modern day surviving branches, that still insist on marrying their 3rd thru 10th cousins as their family tradition dictates, autosomal gene studies reveal that they are remarkably similar similar to each other, having gene variants extremely rare in other populations. So much for us all being the same…

There may be some out there that would like us to believe we now are all just “mutts”, and should continue the process. After all there have to be some who don’t care if they are doomed to serfdom to the new feudalism elite lords. But those in the know of their ancestry know better…

Thoroughbred horse breeding clearly reveals how maintaining one’s ancestral genetic heritage keeps their genomes unique traits intact instead of diluting to non distinquishment. ALL modern Thoroughbred champions descend from just four outstanding progenitor horses from a few centuries back. Those modern Thoroughbreds with too much out breeding are the ones not ending up the winners. That’s how it really works…

LikeLike

Richard Conniff said

As long as you understand that what you are advocating is eugenics, with all its historical baggage of bigotry.

LikeLike