The great primatologist Frans de Waal died last week, of stomach cancer, to the great sadness of his many admirers, myself among them. His radically different view of primate behavior, and his gift for writing about it gracefully in a series of popular books, have placed him among the leaders of a quiet revolution in our ideas about the animal world and about ourselves. Harvard University biologist E. O. Wilson credited de Waal with “moving the great apes closer to the human level than could have been imagined as recently as two decades ago.” Anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, once a skeptic, later came to regard herself as one of de Waal’s “biggest fans” and said his description of the tactics primate societies use to stay together “in spite of their dominance-seeking and even murderous tendencies was terribly important, most especially if we want to understand humans.”

I spent a few days with de Waal in 2003, researching a profile of him for Smithsonian Magazine. (Parts of it later turned up in my book The Ape in the Corner Office.) The first day in the observation tower overlooking his study subjects, I was watching de Waal closely, as any reporter would do in the course of note-taking. “You’re not paying attention to the apes!” he remarked. “I’m paying attention to the main ape,” I replied. He laughed and we got along well thereafter, and of course I did also pay attention to his study subjects. Here’s that profile. I hope it brings back your own memories of an inspired and inspiring observer of the natural world.

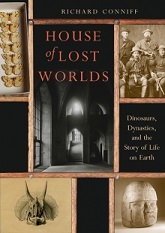

By Richard Conniff

As in a good soap opera, chimpanzee life is anything but gentle, and, his interest in peacemaking notwithstanding, that suits de Waal just fine. On this lazy spring afternoon, he sits watching his study animals from a boxy yellow tower beside an open-air compound, part of the Yerkes National Primate Research Center at Emory University in Atlanta, where de Waal is a psychology professor. Below, one chimp strolls past another and deals out a slap that would send a football tackle to the emergency room. A second chimp casually sits on a subordinate. Others hurl debris, charge, bluff and displace one another. One chimp lets out an outraged waa! and others join in till the screaming swirls up into a cacophony, then dies away.

De Waal, now 55, going gray at the temples, in round, wire-rimmed glasses and a “Save the Congo” T-shirt, smiles down on the apparent chaos. “Growing up in a family of six boys, I never looked at aggression and conflict as particularly disturbing,” he says. “That’s maybe a difference I have with people who are always depicting aggression as nasty and negative and bad. I just shrug my shoulders and say, ‘Well, it’s a little fight. As long as they don’t kill each other.’” And killing members of their own troop is something chimpanzees rarely do. Their lives are more like one of those marriages where husband and wife are always squabbling, and always making up.

“Growing up in a family of six boys, I never looked at aggression

and conflict as particularly disturbing”

De Waal got his start in biology as a child wandering the polders, or flooded lowlands, in the Netherlands, and bringing home stickleback fish and dragonfly larvae to raise in jars and buckets. His mother indulged this interest, despite her own aversion to seeing animals in captivity. (She was the child of pet shop owner and joked that the gene had skipped a generation.) When her fourth son briefly considered studying physics in college, she nudged him toward biology. De Waal wound up studying jackdaws, members of the crow family,which lived around (and sometimes in) his residence. Jackdaws were among the main study animals for de Waal’s early hero, Konrad Lorenz, whose book On Aggression was one of the most influential biological works of the 1960s.

Like many students then, de Waal wore his hair long, and sported a disreputable-looking fur-fringed jacket, with the result that he flunked a crucial oral exam. The chairman of the panel said, “If you don’t have a tie on, what can you expect?” De Waal was furious, but during the next six months preparing for his makeup exam, he got his first chance to do behavioral work with chimpanzees. This time he passed the exam, then threw himself full-time into captive primate studies. Eventually he obtained three different degrees at three different universities in Holland, including a PhD in primatology. He continued his research with chimps at the Arnhem zoo, then spent ten years studying macaques as a staff member at a primate center in Madison, Wisconsin.

Since 1991, he has divided his time between research at Yerkes and teaching at Emory. At Yerkes, the chimpanzee compound for de Waal’s main study group, FS1, is an area of dirt and grass half again as large as a basketball court, enclosed by steel walls and fencing. The chimps lounge around on plastic drums, sections of culvert pipe and old tires. Dividing walls angle across the open space, giving the chimps a chance to get away from one another. (The walls, says de Waal, “let subordinates copulate without getting caught by the alpha.”) Toys include an old telephone book, which the chimpanzees like to shred as a form of amusement.

It is, de Waal acknowledges, a completely artificial environment. Unlike chimps in the wild, his charges don’t spend seven hours a day foraging across their home range, they face no competition from outside groups, there are no immigrants or emigrants, and because of a worldwide surplus of captive chimps, birth control is mandatory. Captivity also reduces the power difference between males and females; females who live together defend one other against male aggression. “But the basic psychology of the chimpanzee and the basic behavioral repertoire are still there,” he says.

Captive studies also offer one crucial advantage: “You have control and you can see more,” says de Waal. In wild studies, it’s often a matter of luck whether you find the animals in the first place, “and it’s tricky to see when they have a fight, because they tend to run into the underbrush. So to follow what happens after a fight is almost an impossibility.” Students of captives used to say that research in the wild was anecdotal and unscientific; the wild researchers in turn said captive work had nothing to do with how animals really live. But the two sides now often collaborate. “I look at it that we need both,” says de Waal.