How Tibetans Handle Thin Air

Posted by Richard Conniff on January 18, 2014

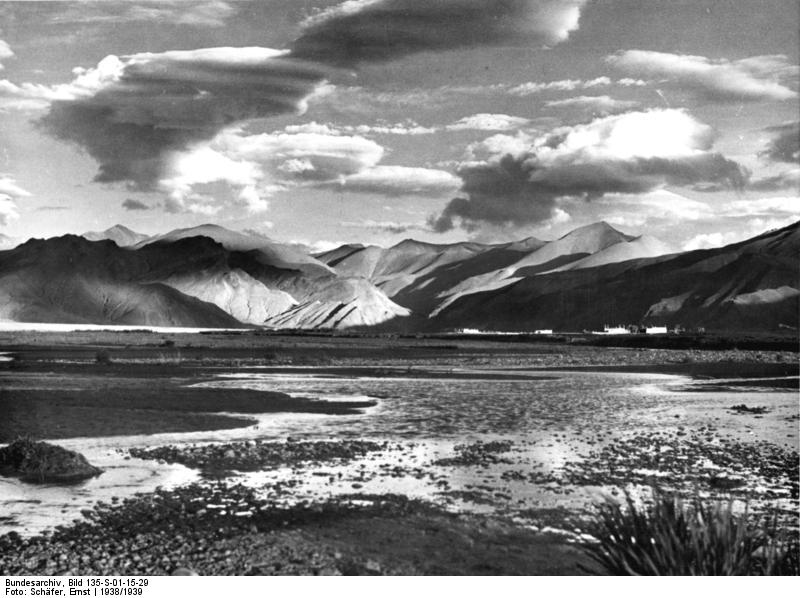

Everything’s black and white because it’s so damned hard to breathe up here. A Tibetan landscape, from a 1938 German expedition (Photo: Ernst Schäfer)

When I was trekking in the Himalayas on an assignment some years ago, I was dismayed by how nimble the locals seemed at high altitude, and how plodding I felt by comparison. But now I have an excuse: I’ve just come across studies showing that their EPAS1 is better than the stuff I inherited from my potato-picking lowland Irish ancestors.

This finding, originally published in 2010 in Science and in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, raises a lot of questions: Why aren’t Tibetans world-class marathoners? And is this genetic quirk part of the reason upland Kenyans are? What about the Bakongo people who outpaced me above 16,000 feet in Uganda’s Mountains of the Moon? Is there a genetic factor there, too. Or am I just a wuss?

Here’s how Cian O’Luanaigh reported the finding at the time in The Guardian.

A gene that controls red blood cell production evolved quickly to enable Tibetans to tolerate high altitudes, a study suggests. The finding could lead researchers to new genes controlling oxygen metabolism in the body.

An international team of researchers compared the DNA of 50 Tibetans with that of 40 Han Chinese and found 34 mutations that have become more common in Tibetans in the 2,750 years since the populations split. More than half of these changes are related to oxygen metabolism.

The researchers looked at specific genes responsible for high-altitude adaptation in Tibetans. “By identifying genes with mutations that are very common in Tibetans, but very rare in lowland populations we can identify genes that have been under natural selection in the Tibetan population,” said Professor Rasmus Nielsen of the University of California Berkeley, who took part in the study. “We found a list of 20 genes showing evidence for selection in Tibet – but one stood out: EPAS1.”

The gene, which codes for a protein involved in responding to falling oxygen levels and is associated with improved athletic performance in endurance athletes, seems to be the key to Tibetan adaptation to life at high altitude. A mutation in the gene that is thought to affect red blood cell production was present in only 9% of the Han population, but was found in 87% of the Tibetan population.

“It is the fastest change in the frequency of a mutation described in humans,” said Professor Nielsen.

There is 40% less oxygen in the air on the 4,000m high Tibetan plateau than at sea level.

Read the rest of that article here.

A 2012 followup study in PLOS ONE found that Sherpas, the celebrated Himalayan mountain climbing population, has the same blood profile (average level of serum erythropoietin) as 3440 meters (11,286 feet) as their lowland counterparts at 1300 meters (4265 feet). And a 2013 study broadens these results to high-altitude peoples in the Andes.

Where–thank you, Ireland!–I have also experienced a passing bout of high-altitude nausea.

Dogs Have Evolved to Be With Us Even In Thin Air « strange behaviors said

[…] month I posted a story about studies demonstrating that both Tibetans and Sherpas, the celebrated Himalayan climbers, have […]

LikeLike